Debating the Popular Messages of Protests in the Bulgarian Media Ecosystem (2013/2018)

Table des matières

Texte intégral

1Abstract

The study aims to compare the images of the Bulgarian civil protests in 2013 and 2018, reflected by traditional media, social media and social networks. The main research question is to explore the transformation, which has occurred in the communication process over the years between the maturing Bulgarian civil society and the elites in the context of the Internet based environment.

Key words: media ecosystem, social protests, images

Résumé

L’objectif de cette étude est de comparer les images de protestations civiles bulgares reflétées par les médias traditionnels, les médias sociaux et les réseaux sociaux. Il s’agit d’étudier la transformation qui est intervenue dans le processus de communication au cours des années entre la société civile bulgare mûre et les élites dans le contexte d’un environnement virtuel basé sur internet.

Mots-clés : Ecosystème médiatique, Protestations, Images

Introduction

2The turbulent development of information and communication technologies has had a significant impact on the functioning of the national States and further has transformed them into dynamic and transnational economic structures. New media technologies have been viewed through the prism of globalization, although the use of this term (especially in the economic sphere) has been subjected to a number of debates. Resistance against the drive for hegemony on the part of the most advanced countries over the rest of the world has been acquiring a ‘bitter edge’. Discussion of the new economic development models has caused mass-scale anti-globalist unrests during the world economic fora at the turn of the new millennium. Furthermore, the high-speed spread of the social media and the social networks enhanced the instantaneous burst of the social movements. All of this has been approached by Castells as nation-wide protest ’revolution of freedom and dignity’ (2012: 20-22). Overall, information and communication environment which is nowadays determined by new media and technologies facilitates users’ participation in the process of generation and dissemination of content. In addition to this, it creates new opportunities for engagement and democratic citizenship.

3Interrelations between the audiences, the traditional and the social media have been reflected in a number of studies. A telling example of the social and new media diffusion is related to the significant protest movements all over the world.

4 Inspired by the Arab Spring events, on September 17, 2011 a string of peaceful protests was launched in the Zuccotti Park in New York, under the slogan ‘Occupy Wall Street,’ prompted by inequality of income in the USA. In support of that movement, Chomsky (2012) noted that the contemporary world has split into ‘plutonomy’ and ’precariat’ in the proportion 1 per cent to 99 per cent. The political slogan ‘We are the 99 per cent,’ who cannot stand the greed and corruption of the 1 per cent anymore, has become popular not only through the traditional, but through the social networks as well. Thousands of demonstrators of the ‘Occupy Wall Street’ movement popularized the stylized plastic mask of the comics character Guy Fawkes by Alan Moore and David Lloyd in 1988, filmed by the Wachovsky brothers in a 2005 anti-utopia ‘V for Vendetta’. The Guy Fawkes mask was also used by the Anonymous movement – a group of hacktivists (term including two notions: hacker and activists) supporting not only the adherents of Wikileaks and ‘Occupy Wall Street’, but also those who defied the 2011 ACTA trade agreement, obfuscating the demarcation lines between theft of intellectual property and sharing of information on the Internet (We, 2011). Activists maintained that internet should stay open and free to everyone and their action plan consisted of three phases: sharing, organizing and mobilizing.

5 Within the framework of less than a year, the spontaneously organized events on social networks contributed to the organization of mass protests across the world and had further managed to redefine the communication processes. The traditional media, especially the radio and TV, in spite of their simultaneous nature, were lagging dramatically behind in the high-speed race for media users’ attention. The Protester – starting from the arab Spring and the ‘Occupy Wall Street’ movement – was proclaimed the person of Year 2011 by the American Time magazine. The leaderless rhisomatic1 Occupy protests across the world on October 15, 2011, were distributed through the Twitter and facebook social networks under the slogan ‘United for Changing the World.’

Bulgarian Social Protests of 2013 and 2018

6The protests in Bulgaria are a telling sign of the activities of the awakened civil society fighting against the monopoly of the oligarchic corporate structures and for integrity of the political parties and the state machine. Although with a small group gathered, Sofia was one of nearly 1000 cities in more than 80 countries which joined the global OCCUPY initiative in June 2012. Self-organized Bulgarian environmentalists, who gathered via social networks, blocked out the traffic in the area of Sofia’s Orlov Most (Eagles Bridge) in order to raise protests against the amendments to the Forestry Law. The law enabled the construction of ski slopes and lifts in previously eco protected areas, thus removing the obligation that the status of the land might be changed for this purpose. Furthermore, it allowed the acquisition of building rights on public land without public tender and for an indefinite time period. The Forestry Law also allowed riparian woodland to be no longer classified as forests, allowing the timber business to cut them down without state approval.

The First Wave of Protests of 2013

7‘Occupy Orlov Most’ became the emblematic agora for social marches in the winter of 2013. The protests which continued in January 2013 in the cities of Sandanski and Blagoevgrad further spread to over thirty other Bulgarian towns. Initially, activists were incited by the high electricity bills and the protests were aimed against the monopolists in the Government-regulated market of electricity, water supply and heating2. Then electricity costs were one of the main expenditures for the Bulgarian citizens. According to the National Statistical Institute data of 2014, 85 per cent of the household monthly incomes were spent on their basic needs, while the average monthly salary in Bulgaria was regarded as the lowest in the European Union – 846 BGN (approx. 432 EUR). The minimum monthly wage – 340 BGN (approx. 174 EUR) – was ten times lower in comparison to that in several EU member states. Twenty-two percent of the labor force was employed on a minimum wage (National, 2014). An addition to this, prices in Bulgaria amounted to 49 per cent of the European Union average (Eurostat, 2013).

8Subsequently the protests escalated against the political system functioning for more than 20 years of the transition period. Protesters symbolically burned their bills. Key motorways and transport routes in the country were blocked; bottles, eggs and stones were thrown against Gendarmerie and Police units, the buildings of the Ministry of Economy and of the National Assembly in the capital of Sofia. A distinctive feature of these protests was a number of self-immolations, including that of the 36-year-old photographer, alpinist and civil rights activist Plamen Goranov from the seaside resort of Varna, which stirred a wide-spread public reaction. Although Plamen Goranov was not the first tragic case, he became one of the symbols of the protesters like the live torches, such as Jan Palach during the Prague Spring in 1968 and Mohamed Bouazizi, whose self-immolation contributed to the rise of the Arab Spring in 2010.

9 February 17, 2013 was the day with one of the most intensive mass protests throughout the country. In more than 35 cities over 100,000 protesters were out in the streets. While initially mainly with social and economic demands, the protests quickly orientated against the political system as a whole. The public tension brought about clashes between the police and the protesters which led to bloodshed and a number of civilians were badly injured. Thus, the problematic economical situation and the social discontent resulted in an early resignation of the government of the center-right CEDb (Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria) political party, which had ruled the country since 2009. President Rosen Plevneliev appointed a caretaker government to serve until elections that were originally scheduled to be held in July 2013, but had to be brought forward.

The Second Wave of Protests of 2013

10The preliminary Parliamentary elections of May 12, 2013 resulted in a hung parliament, with no party having the majority of seats. The voter turnout has been at its lowest since the major political changes of 1989. As the party winning a plurality (97 out of 240 seats), CEDB had the opportunity to form a government, however it could not get support by the other three elected political powers, such as the Coalition for Bulgaria (84), the Movement for Rights and Freedoms (36) and the nationalist political party Attack (23). As a result, the government was appointed with the mandate of the Coalition for Bulgaria (CB), supported by the Movement for Rights and Freedoms (MRF) and holding altogether 120 seats. The quorum was secured by the nationalistic political party Attack – the major opponent of the MRF – a telling political deal.

11On May 29, 2013 – only two days after the appointment of the new government with Prime Minister Plamen Oresharski of CB, protests against it burst out. On June 14, in a matter of hours and again mostly via the social networks (especially Facebook), more than 10 000 people spontaneously self-organized themselves to march in a mass-scale peaceful protest in Sofia. This social movement was inspired against the Parliamentary appointment of the 31-year-old Delyan Peevski to head the Bulgarian State Agency for National Security (SANC – in Bulgarian DANS)3. Being a MRF MP and an owner of a media conglomerate, he was nominated in a non-transparent way by the CB and MRF for that position. The public anger was exacerbated by the fact that in the days leading up to Peevski’s appointment, the Parliament had approved major changes in the legal framework of DANS structures, which gave its head an unprecedented power.

12Although Peevski’s nomination was quickly revoked, the protests against the lack of transparency and integrity of the ruling political power representatives acquired a chronic character. The demonstrations were noted for their use of social networks. In the course of several months in the early evening hours, thousands of Bulgarian citizens took part in the anti-governmental daily demonstrations along the headquarters of the political parties. A mass-scale organizational effect was achieved by using the hashtag #DANSwithme (“Dance with me”) on Facebook and Twitter, which immediately began to attract hundreds of users. This pun, half Bulgarian, half English, associated with the TV show “Dancing Stars”, clearly showed the irony towards the government. The use of social media enabled those who did not attend the events, to follow them virtually. Quickly, with the help of another hashtag #ignorevolen (Ignore Volen) the activists distanced themselves from the hostile actions of Volen Siderov - the leader of the nationalistic political party Attack, and excluded its headquarters from their route.

13The government did not respond effectively to the calls for new elections and public accountability and the protesters have resorted to other means of expressing their anger, such as the initiative of silently drinking coffee every morning in front of the Parliament; randomly blockading key roads; organizing creative happenings, etc. With street performances and abstract art protesters mocked the politicians. Thus the June protests became the heyday of symbolic creativity. The unique spirit of the peaceful protests additionally inspired the broad publics. These unconventional messages were understood easily and were remembered for a long time.

14However, on July 23, because of the intention of the government to not transparently amend the 2013 State budget, demonstrators blockaded the house of the Bulgarian Parliament with trashcans, park benches, paving stones and street signs. A significant number of MPs and ministers were trapped inside the building for more than eight hours. Despite the mounting pressure and the growing people’s discontent, the government largely ignored the protesters and dismissed their claims.

15The government largely ignored the protesters and dismissed people’s claims. On the contrary, a counter-protest in support of the Oresharski cabinet (CB), and against President Plevneliev (who has supported the anti-government protests) – although with much lower attendance – was organized. Supporters of the government insisted that the new political power should be given a chance to work. Both protests and counter-protests took place in other Bulgarian cities as well. National demonstrations in all major cities were also supported by the Bulgarian Diaspora, protesting in front of the Bulgarian embassies and consulates across Europe: Athens, Barcelona, Berlin, Brussels, Dublin, Düsseldorf, Frankfurt, London, Madrid, Munich, Paris, Vienna, as well as in many other major cities all over the world. Some people nostalgically compared the protest summer of 2013 to the public demonstrations at the dawn of the transformation to democracy in 1989-1990. Others saw a difference in that the historical discontent then was aimed at dismantling of the totalitarian political system, while two decades later it was apparently targeting the improvement of the quality of the democratization processes.

16 In spite of the fact that some executive measures for lowering the electricity bills were taken, yet again they did not seem to be sufficient, clearly outlined and sustainable. The Anti-government Information Agency NOresharski!, distributed online, cited the opinion poll by the Alpha Research agency, which pointed out that 51 % of respondents supported the anti-government protests demanding resignation of the government, 33 % supported the counter protests in favor of the government, while 16 % did not support either protest (Noakes, 2005).

17The elections for European Parliament in May 2014 were not favorable for the ruling Coalition of Bulgaria and with no sufficient support by the National Parliament, the Oresharski government was forced to resign after fourteen months of social tension and discontent. A caretaker government to serve until the preliminary parliamentary elections on October 5, 2014 was appointed by President Rosen Plevneliev.

18All of the 2013 protests have been extensively covered and commented by the mainstream media, as well as via social networks. Although the majority of the participants in the social protests remained peaceful, in both cases violence erupted and attracted the attention of the mainstream media. The social discontent in Bulgaria had not any leaders or spokespersons. The Internet enabled activists to plan, plot and co-ordinate the protests at low costs, anonymity (for threat of police detection) and high speed. At the same time they were apparently able to reach a wider audience of potential participants than ever before, and thus were able to spark a ‘rampage’(Pickerill, 2003: 1).

The Protests of 2018

19At the end of 2018 the social dissatisfaction of the high fuel prices and the living standards wass expressed by blocking key highways across the country and paying in coins at the gas stations. There were demonstrations in over 50 towns across the country (Frognews, 2018). One of the most affected motorways was E79, connecting the capital Sofia with Blagoevgrad on the way to the border with Greece.

20People took to the streets calling for the resignation of the government led by PM Boyko Borisov leader of the center-right political party CEDB and for a radical change in the political system.

21On November 11, citizens of Sofia gathered in front of the building of the Council of Ministers shouting slogans such as “Mafia” and “Resign”. The protesters demanded for increasing of the minimum wage to 750 BGN (approx. 383 EUR), the minimum pension to 350 BGN (approx. 179 EUR), the starting salary of a nurse to 1200 BGN (approx. 614 EUR) and for a medical doctor – 2000 BGN (apron. 1023 EUR). In comparison, Bulgaria has the lowest average salary in the European Union, at 575 EUR a month, the lowest minimum wage, at 260 EUR, and the lowest average pension, at EUR (National, 2018). The previous day, citizens of the northern town of Ruse and of the south-western town of Pernik protested against air pollution in their environment. Ruse, which lies on the Danube river border with neighbouring Romania, woke up with its bridge crossing the river to Romania blocked. The protesters stated that by blocking a major European road they wanted the European citizens to become aware of the issue of air pollution in their town. Pernik’s residents’ cleaner air initiative involved a concert held under the slogan ‘Breathe, Pernik’. Representatives of Greenpeace - Bulgaria and ‘Zero Waste’ provided the attendees with information regarding their town’s air and pollution problems.

22Another protest was held by the mothers of children with disabilities. They demanded amendments to legal framework for better social care for these children. On October 16th, the Deputy Prime Minister Valery Simeonov made a public TV statement, referring to the mothers of disabled children as “shrill women” and their descendants – as “supposedly ill children”. The comment was addressed towards the women who were campaigning on a daily basis for several months for a reform in the country’s system of assistance to children with disabilities. Following this statement, the protest erupted demanding Simeonov’s immediate resignation. After he refused to apologize, he also refused to resign from his executive position, until the Prime Minister Boyko Borissov forced him to do so. The mothers of disabled children celebrated the resignation of Deputy Prime Minister Valery Simeonov with traditional Bulgarian horo dance.

Methodology

23The main research question of the study is to explore the transformation, which has occurred in the communication process over the years between the maturing Bulgarian civil society and the elites in the context of the Internet based environment.

24The motivations, expectations and attitudes of the protesters in the years under research are not similar; the ruling parties differ in approaching the democratic values as well. In pursuit of the aim of the study, the analysis specifically sought answers to the messages of the visual images, provided mainly by photographers, reporters and bloggers (Pickerill, 2003:1).

25One of the tasks is to trace how traditional media, social media and social networks are involved and step in as a catalyst in organizing the protests in Bulgaria. Another task is to compare the levels of public trust in traditional media, social media and social networks in times of political turmoil and social discontent between 2013 and 2018.

26Comparative analysis is the study method. It explores the way traditional media, social media and social networks reflect the protests in the country. Messages, delivered through the visual images of the 2013 and 2018 protests outline the essence of the study, stressing on the specifics of the media ecosystem to present the actions of the civil society in the country.

27The object of the research is the behavior of the protesters and how they acted, whether it came to speeches, slogans, staged or spontaneous actions. For this purpose TV, websites, newspapers, social networks and fora were examined.

28The Perlmutter’s (1998) typology, including (1) importance of the event depicted, (2) metonymy, (3) celebrity, (4) prominence of display, (5) frequency of use, and (6) primordiality, was followed (Perlmutter, 1998).

29One of the most characteristic features of protests both in 2013 and in 2018 was that they were largely attended. Thousands of Bulgarians took to the streets. The visual appearance of the mass discontent could be displayed in many different ways. The selected photographs were powerfully memorizing strong and vibrant moments of people's activity.

30This paper focuses on some emblematic, symbolic moments of the protests:

- symbols of fire;

- symbols of funeral ceremonies;

- symbols of performances.

Major Findings

31The social movements of 2013 in Bulgaria were marked by rising outrage and discontent and were centered jointly on asserting economic and political rights. The February protests were primarily engaged in struggle against the high energy prices as well as against austerity measures. Frustrated people, forced into living conditions without security or predictability, went out in the streets to defend the limits of their social existence. They gained the identity of ‘precariat’4. The main grievances and causes of outrage of the June protests were connected with the deficits of the real democracy in the political system, including economic injustice; corporate influence; corruption; lack of transparency and accountability of the government; insufficient surveillance of citizens, etc. Protesters struggled for the quality of the democracy and for social and political rights.

32The protests of 2018 were focused mostly on the integrity of the political elite. They were driven by the demands for social justice, care and protection.

33The Bulgarian social protests in all studied cases were leaderless. People gathered horizontally through decentralized social networks and acted in a direct, participatory democracy of equals, which managed to mobilize simultaneously individuals from different age groups, educational background and social stand. They were united by the desire to freely express their previously misrecognized and neglected identities.

34The spontaneously organized (thanks to the social networks) mass protests have managed to redefine the communication discourse. The traditional media, especially the radio and TV, in spite of their simultaneous nature, were lagging dramatically behind the social media and the social networks in the high-speed race for consumers’ attention.

The Symbolism of Fire

35Fire, or rather burning is a symbol that is persistently present during the February protests of 2013. But unlike mythology, where fire is perceived as a positive force and is associated with progress and light, unlike Christianity, where it is a symbol of the Holy Spirit, during the protests in the country fire was presented with its destructive nature. Burning, in its various forms, usually illustrates the destruction of unwanted. Symbolically speaking, however, this kind of destruction may lead to purification as well. The fire was used as a symbol of the brutal force in the protests of winter 2013.

Setting Fire to EVN Corporate Cars

36On February 10, 2013 a group of protesters burned two cars in Plovdiv, belonging to the Austrian Energy supply company EVN (Energieversorgung Niederösterreich. This was the first of the subsequent series of symbolic actions of that kind, many of which - unsuccessful. In this case fire was used as a symbol of the brutal force of the mob that burst out after long suppression of emotions.

37Burning of Electricity and Central Heating Bills

A similar but much more symbolic was the act of burning electricity and central heating bills. The spontaneous act was much more effective than speeches, chants and slogans. Such acts of ritual burning of the bills supplemented protest actions in almost all the cities where they spontaneously arose.

Photo: Dimana TODOROVA Photo: © George KOZHUHAROV

38(BLITZ agency) (Capital newspaper)

Burning of the Constitution in Plovdiv

39Setting on fire was not limited to corporate cars and energy bills only. On February 25, 2013 in Plovdiv the protesters against monopolies reached more than 10 000. The procession passed along the main boulevards and practically blocked the city traffic. A copy of the Constitution was burned as an act of discontent against the status quo and the restrictions of the civil rights.

Burning of Effigies of Politicians

Symbolic act, which took place in several cities, was the burning of effigies of politicians. The significance of this effect quite clearly and unequivocally showed the attitude of the people towards the politicians. Such funeral burns of effigies were performed in many cities.

Group Photo: Impact Press

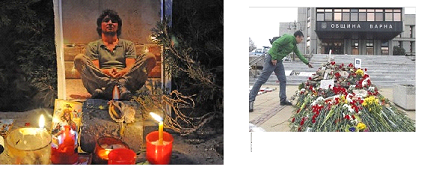

Self Immolation of Plamen Goranov

Saturated with symbolism and protest against the ruling politicians and in particular - against the then mayor of Varna Kiril Yordanov, was the self immolation of the 36-year-old photographer and mountaineer Plamen Goranov on February 20, 2013. Although the mayor resigned, after his death Plamen Goranov became a symbol of the protests. He was compared with Mohammed Bouazizi, whose self immolation ignited the start of the ‘Arab Spring’, as well as with the Czech student Jan Palach, who set himself on fire during the ‘Prague Spring’ of 1968.

40The self immolation of Plamen Goranov remained the most emblematic, although he was followed by other desperate people who committed suicide by self-immolation.

Photo: Mario EVSTATIEV (inews.bg)

41Dimitar Dimitrov - one of the many self-immolators in Bulgaria, who miraculously survived, described his attempt to commit suicide in public as a form of protest against the social injustice in the country.

42Interviewed by BBC reporters, he explained that he wanted to sacrifice himself for the sake of better life in the country. His desire was aimed at the world to understand the predicament of the poorest member state of the EU. BBC released two reports, entitled: “Bulgaria prays for no more suicides” and: “Poverty in Bulgaria brings more people to suicide” (BBC, 2013).

43The media, and especially the TV coverage of the series of multiplying protest cases of self-immolation or self-infliction of bodily injuries, has prompted the Council for Electronic Media to publish a special Declaration addressed to providers of Tv Services. With this Declaration the regulatory authority appealed to the Bulgarian media to show more concern for the life and health of the citizens, while covering the civil protests without underestimation of the right to information and within the framework of their editorial independence (Council, 2013).

The Symbolism of Funeral or Horror Ceremonies

44‘Funerals’

The “funeral” of the monopoly of the electricity distribution companies on February 17, 2013 in Varna became one of the key symbols in the February protests. This act displayed lack of willingness for dialogue. The symbolic ritual showed the decisiveness of the participants in the ceremony “to destroy and bury” the monopoly.

45Months later similar ritual funeral ceremony was held in Sofia but this time the protesters buried the political parties. Under the tune of a popular funeral march the participants carried a black coffin with inscription of the names of the main political parties in the country.

Photo: BGNES

‘The System Kills Us’ – 2018

'The System Kills Us', a networked social movement in Bulgaria, was born after a series of offensive verbal attacks and aggressive actions of the former Vice Prime Minister of Bulgaria, Valery Simeonov.

Photo: bTV

The community of mothers of children with disabilities launched an online movement in 2015. They managed to mobilize and organize eight protests within three years, which became popularly known as ‘the protests of the mothers’. Being neglected with their ‘personal’ problems for years and years, the mothers realized that their personal problems are actually a problem of the state. That is why they started tent protests, camping in front of the National Assembly in the capital city Sofia on June 1, 2015. People from other cities joined the protests and the movement grew to a national level. During the protests people were wearing black T-shirts with the slogan ‘The System Kills Us’.

46“We realized that if we wanted a decent life for our children so that they would be an equal part of the society, our efforts should be focused not only on social policy reforms for people with disabilities. Because not only the social system kills us – it is also the health system, the education system, and court, and...” explained the mothers of children with disabilities in the official Facebook page (System, 2018).

47'The System Kills Us' cannot be understood as a leaderless movement or an instance of networked individualism. It is the exiting community of activists that used digital media to upscale their activism by creating an open Facebook page, entitled 'The system Kills Us'. On June 23, 2018 the page has reached 13k likes and 15k followers.

Symbols of the Performance

48The June protests of 2013 were characterized mainly by their peaceful nature as a whole, as well as with the symbolic creativity of the protesters’ actions.

49Typical of symbolic signs in general is that they bring in public ready messages, moods and attitudes. Symbols are indicating a special attitude to an object, idea, religion, image, etc. Developed in different environment, they are upgraded and adapted to the case. Presented peacefully, symbols have much more understandable messages than the demands of an angry fanatical crowd. Performances help better in attracting followers and have long-time effect on the audiences.

50The symbolism of the June’13 protests was far more sophisticated and carefully directed in some cases. Some of the symbols included the impersonation of famous paintings; paraphrase of existing and already used slogans and messages; puns; theatrical sketches, etc. Artistry and creativity in the June protests displayed a new face of the people, far more conscious and confident, ready to fight for their cause with a smile.

The Symbol of the Painting La Liberté guidant le peuple by Eugene Delacroix

51A telling example of street performance in Sofia was the symbolic “revival” of the picture Liberty Leading the People by the French painter Eugene Delacroix. Originally this picture has been dedicated to the July Revolution of 1830 in France. The performance in Sofia was organized on the eve of July 14 - the French national holiday in honor of the French Ambassador in Bulgaria Philippe Autie. He and his colleague, the German Ambassador in Bulgaria Matthias Hoepfner, supported the protesters. Both diplomats proclaimed that oligarchic political model is incompatible with the EU values and policies (Dir.bg, 2013).

Photo: © Sofia Photo Agency

52The Presence of Children in Protests

53One of the key features of the June protests of 2013 was the demonstratively non-confrontational manner of their conduct. Protesters took their children to the marches namely to express the peaceful character of the events. Moreover, children were a clear symbol of the purity and fairness, so much cherished for the future of the country.

54June's protests were not just spontaneous outburst of the people’s discontent, but a desire to improve the quality of democracy associated with expectations to improve the integrity of the politicians. “The protesters in the streets of Sofia showed unique self-organization aiming at procession to pass peacefully and without incidents. Moreover, the peaceful protesters themselves alerted the police about suspicious persons that behaved provocatively and aggressively. The police responded immediately and asked provocateurs to leave the protest” (24 Hours, 2013).

55A photo, showing how a young father is feeding his baby during the protests, became emblematic image of the daily demonstrations in June’2013. This photo was quickly disseminated on a large scale via Facebook (Dnevnik, 2013).

Photo: 24 Hours Daily

56Students’ Performances

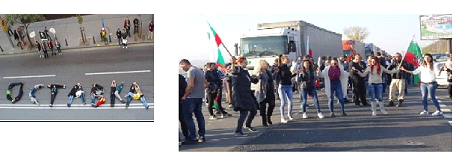

57Students from the National Academy of Theatrical and Film Art displayed their messages interrupting regularly on a daily basis during the summer of 2013 the traffic of one of the main streets in the capital of Sofia. The idea of the performance was connected with the transformation of the young people from passive witnesses to active participants in the social matters of the country. The final of the performance was memorable – they formed with their bodies the word “Resignation”.

Photo: Veliko Balabanov Photo: BGNES

58A similar symbolic act was the demolition of a 30-foot high cardboard Berlin wall in front of the German Embassy in Sofia.

59The ‘Horo’ Dance

60The mothers of disabled children celebrated the resignation of Deputy Prime Minister Valery Simeonov after their protest in 2018 with traditional Bulgarian horo dance.

61In the demonstrations horo dance is part of the protest attributes - flags, slogans, signs. On the road blockades along the border with Greece, on the main roads or on the central streets of Sofia the folklore is inspiring element for the protesters. It is so, mainly because the ‘horo’ dance is a symbol of the collective spirit, an important part of the Bulgarian traditional culture, which creates the feeling of unity and cohesion. It is also a metaphor of power and attribute of the festivity.

Concluding Words

62Over the last ten years there have been serious changes in the protesting culture in Bulgaria and in the communication between protesters and the ruling party in the country. As a result it is observed a noticeable maturation of the Bulgarian civil society and certain differences in the way the protesters communicate with the Government. The distinction is noticed in the variety of the protesters' symbols, reflected by the Bulgarian mass media.

63The social protests at the beginning of 2013 were more violent than those in middle of 2013 and in 2018. The protests in Bulgaria in 2013 (winter) and those in 2018 started as a demand for economic justice.

64The symbols of the winter protests in 2013 were numerous acts of burning: the EVN corporate cars, the electricity bills and the politicians’ effigies. The most radical acts against the social injustice included several acts of self-immolations and bloody clashes in front of the Parliament building. After these scenes, broadcasted by the mass media worldwide, the Bulgarian government resigned and preliminary elections were held. .

65The protests in summer of 2013 started as a moral corrective of the ruling Government. Their symbols were theatrical performances, children presence at the protest marches, music concerts, puns (#DANSwith me), etc. However, because of the intention of the government to not transparently amend the 2013 State budget, demonstrators blockaded the house of the Bulgarian Parliament with trashcans, park benches, paving stones and street signs. Despite the mounting pressure and the growing people’s discontent, the government largely ignored the protesters and dismissed their claims, but it was forced to resign after fourteen months of social tension and discontent.

66The 2018 protest wave against high fuel prices and lack of legal reform for children with disabilities was not able to destroy the political stability although one of the prime-ministers had to resign. The symbols of the protests in 2018 were the traditional ‘horo’ folk dance; paying in coins at the gas stations; blocking major highways.

67Protests in 2013 and in 2018 were leaderless and have been organized via social media. In the long-term these protests resulted in public awareness, which has to be prioritized by the ruling powers in the future.

68Acknowledgements

The paper is developed within the framework of the COST Action CA 16226: SHELD-ON, supported by the research project KP-06-COST/5 – 18. 06. 2019 of the Bulgarian National Scientific Fund and the Program Young Scientists and Post Docs of the Bulgarian Ministry of Education and Science.

Bibliographie

BBC (2013). Bulgaria Prays to Have No More Suicides. http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-22039182

Council for Electronic Media (12.03.2013). Declaration Regarding the Activities of Providers of TV Services in Connection with the Multiplying Cases of Protest in the Form of Self-immolation and Self-inflicting of Bodily Injuries. htt p: www.cem.bg/view.php?id=3246

Castells, M. (2012). Networks of Outrage and Hope. Social Movements in the Internet Age. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Chomsky, N. (2012). Occupy. New York: Zuccotti Park Press.

Dir.bg (08.7.2013). Germany and France Support the Protest against the Oligarchy in Bulgaria. http://dnes.dir.bg/news/Germania-frantzia-izbori-2013-14379384

Dnevnik (03.09.2013). Shots of Other Life of the Protesters. http://www.dnevnik.bg/bigpicture/2013/09/03/2126418_kadri_ot_drugiia_jivot_na_protestirashti/

Eurostat (2013). Comparative price levels. Retrieved March 12, 2014 from http://epp.eurostat .ec.europa.eu/tgm/table.do?tab=table&init=1&plugin=1&language=en&pcode=tec00120

Frognews (2018). Over 50 cities in Bulgaria are protesting today. https://frognews.bg/novini/nad-50-grada-balgariia-izlizat-protest-dnes.html

National Statistical Institute. (2018). Household income, Expenditure and Consumprtion. https://www.nsi.bg/en/content/5680/annual-data

National Statistical Institute. (2014). Short-term Statistics on Employment and Labour Costs. http://www.nsi.bg/otrasalen.php?otr=51&a1= 2005& a2=2006&a3=2010&a4=2011#cont

Noakes J., H. Johnston (2005). Frames of Protest: A Road Map to a Perspective. USA: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, INC.NOresharski! (2013). 51 % of Bulgarians support anti-government protests. http://noresharski.com/?lang=en

Perlmutter D. (1998). Photojournalism and Foreign Policy: Icons of Outrage in International Crises. Westport: Praeger.

Pickerill J. (2003). Cyberprotest - Environmental Activism Online. Manchester University Press.

System Kills Us (2018). https://www.facebook.com/SystemKillsUs/

24 Hours Daily (20.06.2013). See the Children of the Protest). http://www.24chasa.bg/Article.asp?ArticleId=2076114

We Are Legion. The Story of the Hacktivists (2011). http://wearelegionthedocumentary.com/hacktivist-timeline

Notes

1 The term rhisomatic was introduced by the French post-modern philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari to denote the acts of non hierarchical multitude described in their two-volume work Capitalism and Schizophrenia (1972–1980).

2 Electrical power distribution in Bulgaria was managed by a state-owned monopoly until 2005, when the government sold 67 percent of it to three foreign companies - German E.ON, Austrian EVN Group and Czech ČEZ Group. In 2011, E.ON sold its Bulgarian branch to the Czech Energo-Pro, and on the next year the state sold its stakes in ČEZ. ČEZ and Energo-Pro virtually operate as private regional monopolies whose activities are monitored by the State Commission for Energy and Water Regulation (SCEWR). The state also sold its power distribution infrastructure to them and lost control over the management of profits.

3 Bulgarian State Agency for National Security (in Bulgarian the abbreviation ‘DANS’ is used as a pun for ‘dance’).

4 Noam Chomsky notes that the contemporary world has split into ‘plutonomy’ and ’precariat’ in the proportion 1 % to 99 %

Pour citer ce document

Ce(tte) uvre est mise à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International.