- Accueil >

- Browse this journal/Dans cette revue >

- Minorities and social networks/Minorités et réseau... >

Unheard Voices and Vulnerability of East Asian Female Students in the U.S.

Case Study in a Rural Non-research University

Abstract

This article explores the experiences of East Asian female students studying in the rural U.S., where the population is highly homogeneous. Drawing from a case of rural non-research university in the Midwest, this study explores the effect of stereotypes and prejudice on East Asian female student’s academic and social adjustment. The focus is on the challenges they are confronted with, and the way their cultural identity and gender affects their study abroad experiences. Through qualitative methodology, the inquiry is made through interviews, surveys, and observations of 26 young women from East Asia and 33 surveys of American students. Results bring to light the severity of sexual harassment, discrimination and the vulnerability of this group.

Table des matières

Texte intégral

Introduction

1 Over 800,000 Asian students are studying in the U.S., many of whom have made numerous sacrifices for the opportunity to get an American higher education. There are also numerous literature on East Asian student difficulties in adjustment to the Western culture (Cheng, Leong, & Geist, 1993; Fritz, Chin, & DeMarinis, 2008; Poyrazli, Kavanaugh, Baker, & Al-Timimi, 2004; Redmond & Bunyi, 1993). During their study abroad, they are confronted with language barriers, adjusting to a new diet, a new physical environment, a different education system, and having various legal restrictions placed on them depending on their immigration status. One of the challenges in surviving and adapting to the new environment is overcoming culture shock. Overcoming culture shock is imperative for adapting to the new environment and Oberg (1960) suggests the cure for culture shock is in getting to know the local people. Other scholars also have confirmed that the interaction between the new comers and the host populations plays a major role in the process of adaptation. Kim (2001) demonstrated the effect the host environment conditions have on the intercultural communication, and argues the importance of ties with host nationals achieving integration of foreigners into host culture. Ward, Bochner, Furnham and Ward (2001) also note the importance of the social, political, economic and cultural factors in the society of settlement. There is a mutual exchange between the attitudes of the host nationals and ethnic groups, this is often moderated by the popular opinion (Berry & Kalin, 1979). In his later works Berry (2009) further argues that not everyone will acculturate and become part of the dominant group. He suggests that there are four strategies for ethno cultural groups as they negotiate their identity: 1) separation, 2) integration, 3) assimilation, 4) marginalization. Assimilation is when the individual chooses to actively immerse into the host culture seeking daily interaction, while rejecting or neglecting their own cultural identity. Integration is when the individual preserves their own cultural identity and at the same time participates and interacts with host society. Separation is when the ethnic cultural identity is tightly held onto, and the host culture is rejected, commonly through avoidance of interactions. The final strategy is marginalization, when neither ethnic cultural identity is maintained nor interaction with host culture is avoided, often due to exclusion or discrimination (Berry, 2009). Berry further notes that integration is only possible when the dominant society is open and inclusive of foreigners. The argument presented in this article supports this thesis. We argue it is extremely difficult if not impossible to integrate into a host environment that is perceived as hostile.

2 However, there are people bound to point to the individual as well as other factors that might be argued to be more important. One of which is personality, and the most precise characteristics for successful cultural adaptation are: cultural empathy, open-mindedness, emotional stability, flexibility, and social initiative (Van Der Zee & Van Oudenhoven, 2000). So-called ‘multicultural personality’ (MP) is supposed to be highly predictive of a student’s ability to adapt to the new environment. Although personality is likely to affect many aspects of our lives, the new environment is also an important factor. Therefore, it can be argued that, although MP is important, it is hard to adjust to a hostile environment even if an individual has all the characteristics of MP.

3 Other factors that are commonly noted are students’ self-efficacy and self-determined motivations also help them to integrate into American society. English language proficiency also affects Asian international students’ ability to adapt to the U.S., along with their academic success and social interactions (Fletcher & Stren, 1989; Perrucci & Hu, 1995; Trice, 2004). Language barriers and different learning styles can cause difficulties during class discussions and in intercultural communication (Kim, 2006; Perrucci & Hu, 1995; Hsu, 2011). Furnham and Bochner (1986) suggested a necessity to focus on social skills and culture learning models, as communication competence also plays a major role in adaptation (Furnham, 1993). Another obstacle is the difference in communication styles and lack of knowledge about American social norms (Barratt & Huba, 1996; Lee, Kang, & Yum, 2005; Rose-Redwood, 2010; Swagler & Ellis, 2003; Zhou, Frey, & Bang, 2011). All these problems make it more difficult for Asian students to make local friends, which leads to loneliness and isolation. However, if the host environment is welcoming and inclusive all of these variables are much easier to overcome. Regardless of the English proficiency or communication competency it is more difficult to communicate with local population if they do not want to communicate with foreign nationals or are hostile toward them. Numerous studies have been done in the process of coping with acculturation stress, and according to a meta-study that reviewed 19 years of research on acculturation, the factors that acted as predictors of psychological symptoms were categorized as stress, social support, English language proficiency, length of residence, acculturation, personality, self-efficacy, country of origin, and gender (Zhang & Goodson, 2011). In adapting to a new environment, other difficulties such as role changing and racial discrimination (Fumham & Bochner, 1986) are at times unavoidable and depend on the host environment. Therefore, although international students might have the multi-personal characteristics, English competency, the proper motivation and confidence to succeed, we argue it is the conditions of the country of settlement that play the biggest role in the process of adaptation. In particular the attitudes of Americans toward East Asian women would play a major role in the process of their adaptations.

The History of Prejudice and Asian Stereotypes in the U.S.

4There are both positive and negative Asian stereotypes held by Americans. Positive stereotypes have demonstrated to cause negative emotion, such as anger and give a sense of depersonalization in Asian Americans (Siy & Cheryan, 2013). One of the earliest Asian stereotypes is “Yellow Peril,” which comes from the late 19th century when workers from different Asian countries immigrated to the USA, Australia, Canada, and New Zealand (Wu, 2002). In the U.S., the white working class was strongly against Chinese immigration because they took jobs from native-born Americans and agreed to work for lower salaries (Kearney & Knight, 1878). The Yellow Peril xenophobia led to the Chinese Massacre of 1871 when white Americans lynched 20 Chinese. Workingmen's Party of California leader, Denis Kearney, was famous for concluding all his speeches with “…and whatever happens, the Chinese must go!” (Gyory, 1998; for more literature on Asian Mystique see Prasso, 2005).

5While in the 1980s Japan was seen as an “economic threat” by North America and Western Europe, in the 1990s its image began to change and China became a new threat and instead of “Japan bashing,” new expressions appeared such as “Japan passing” or even “Japan nothing” (Akuto, 1994; Ishii, Kaigo, Tkach-Kawasaki, & Hommadova, 2015). However, according to the BBC World Service held in 2012, 2013, and 2014, the image of Japan was number one among Asian countries, having a mainly positive impression. China has been seen as “public enemy #1” in the last few years, and its military and economic threat is perceived most strongly among other Asian countries (Ishii, at al., 2015). Korea was the least familiar and least popular according to the BBC World Service held in 2014. The attitude towards Asians can also be affected by the age of hosts, since young Americans are more familiar with Asian countries than older ones (Ishii et al., 2015). Furthermore, older respondents have more negative perceptions of Chinese products (Ishii et al., 2015).

6East Asians are often stereotyped as a “model minority,” which means they are thought to be hardworking, politically inactive, polite, and intelligent. This stereotype is often common at the U.S. schools, too, where teachers consider Asians as “model students” (Wong, 1980). A study by Lee (1996) bolsters these findings, and asserts that most of the American students consider Asian students to be “geniuses,” “uninterested in fun,” “nerdy,” and “competitive,” which supports the “model minority” myth.

7Asian people are often stereotyped by U.S. media (Frith, Cheng, & Shaw, 2004) and cinematography; for example, before the 1990’s, Asians used to act as villains, or laundromat or restaurant owners (Harris, 1999). In advertisements, Asians are portrayed as submissive, devoted to work, in business suits, and are advertising technology-based products (Taylor & Stern, 1997; Taylor, Lee & Stern, 1995). Furthermore, Japanese students were found to be less impulsive and more timid than American students according to Hama and Plutchik (1975). The stereotypes of Asians held by the host populace is prominent in exploring the interactions between Asians and Americans. However, Asian women are not only confronted with stereotypes about Asians, but also with stereotypes associated with Asian women, and in order to comprehensively understand the position of East Asian female students in the American higher education, it is necessary to first comprehend the stereotypes regarding them within the larger American culture.

Image of Asian Women in the U.S.

8The history of Asian women stereotypes is rather long. During the “Yellow Peril” period in the U.S. (1800’s), Chinese women were viewed as dangerous and immoral (Song & Moon, 1998). The term “Dragon Lady,” which became a definition for such kinds of Asian women, first appeared in Milton Caniff’s comic strip “Terry and the Pirates” in 1935 (Hoppenstand, 1992). The stereotypical “Dragon Lady” is powerful, lustful, and threatening. This image was related to such famous Asian women as Soong Mei-ling, also known as Madame Chiang Kai-shek, Chinese-American actress Anna May Wong, and anachronically to Chinese Empress Dowager Cixi (Seagrave & Seagrave, 1993).

9During World War II, American soldiers interacted with East Asian women and perceived them as obedient and passive, yet sexual (Uchida, 1998). As Uchida stated, “Whether as prostitutes or perfect wives, the U.S. soldiers' location in the Asian countries and their particular encounters with women were crucial in the creation and diffusion of the Oriental Woman in the United States.” (Uchida, 1998, pp. 165). The term “Asian fetishism” appeared in the late 20th century in the USA and later was defined as "the sexual objectification of people of Asian descent, typically females, who are objectified and valued not for who they are as people, but for their race or perceptions of their culture.” (Ruiz, 2009). David Henry Hwang used the term “yellow fever” in the afterword to his play “M. Butterfly” to describe men's addiction to Asian women. He writes that the stereotype of Asian women as “best wives,” obedient, and domesticated is not an anachronism, and can be found in numerous American “bride catalogues” and call-girl services, with a wide selection of exotic and “trained in the art of pleasure” girls (Hwang, 1986).

In the American advertisements, East Asian women are portrayed as “servile” and “passive, sexual objects” (Wang & Cooper-Chen, 2010). These images derive from Japanese geisha culture and massage parlor ads (Wang & Cooper-Chen, 2010). Such depictions of Asian women being exotic and eager to serve men can often be seen in U.S. movies (Memoirs of Geisha, Sayonara, M. Butterfly, etc.). Besides, some Asian women state that when dating American men, they feel that Americans are interested not in their personality but rather in the generalized image of an Asian woman and Americans’ fantasies about them (Sharp, 2010). Asian women are desirable because of their mysteriousness, pliability, agelessness, girliness, exoticism, and servility. As was noted above, in the U.S. there are online dating services where American men can find “classy, desirable, loving, sweet, and gentle” Asian girlfriends. They are described as loyal women who tend to retain their femininity and are comfortable to be with - unlike white American women who have become too masculine and competitive (Sharp, 2010). That’s why women need to be sure that Western men don’t expect them to be just an exotic and comforting “oriental flower” (Sharp, 2010).

10Therefore, while Asian males hold a rather positive image in the eyes of Americans, Asian women can face different forms of sexism. In addition to the stress caused by studying abroad, being a minority can affect Asian female students’ adjustment. Racial minorities experience daily stress caused by discrimination, and the minority status adds additional psychological stress (Smedley, Myers, & Harrell, 1993). Furthermore, for students who come from racially homogeneous countries, such as Japan and Korea, exposure to diversity as well as being a racial minority in the U.S. can contribute to adjustment stress (Ito & Morales, 2003). There are limited studies looking at how stereotypes and prejudice affect the experiences of East Asian female students in the U.S., and almost none about the experiences in the rural or semi-rural U.S. One study explored discrimination, prejudice, stereotypes of Japanese female students in the rural U.S., and coping with these problems by avoidance (Bonazzo & Wong, 2007). With four participants, they found there were stereotypes unique to the Japanese that were related to samurai and origami. They found that some Americans in rural U.S. tend to lump all Asians together or associate all Asians ethnically with Chinese. This study provides valuable insight into the area that is not well explored, but with a few number of participants and no other Asian female students to compare with, this still leaves open a wide gap for the understanding of Asian female experiences in the rural U.S. In summary, the purpose of this study is to explore the discourse of gender and ethnicity in the experiences of Asian students studying in the U.S. The main research questions of this study are:

11RQ1: How does gender affect the lives of East Asian female students in the U.S.?

RQ2: What kind of discriminations, prejudices, and stereotypes do East Asian females experience in the rural U.S.?

Methods

12 The majority of the data derived from the interviews with 20 female students from East Asian countries studying in a semi-rural Midwestern non-research university in the U.S. and six online anonymous surveys. The students were from Japan, Korea, China, Malaysia (ethnically Chinese), and Taiwan, and represent many separate academic departments. The ages of participants ranged from 19 to 25 years old, and they were part of a larger research project of 38 participants aimed at examining the adjustment of Asian students to the semi-rural U.S. Throughout one year of fieldwork, numerous observations were made on the lifestyle of the participants, and more than one interview was conducted with available participants. The students who were studying full time and were enrolled as undergraduate students, as well as short-term exchange students, were recruited through an announcement by the faculty of the university and through the cultural student organizations of the Korea and China Club. The observations took place during study sessions, social gatherings at students’ apartments, school events, and school organization meetings. Upon the return of the exchange students to their home countries, four female Japanese students were required by their home institutions to submit an official report on their studies abroad. These students contacted the researcher, offering to send a data copy of these reports for use in this study. These documents provided invaluable insight into how the experiences of study abroad are framed and presented to home institutions. They are also made available to future students planning to study abroad at the same institution.

13 Additional data was gathered from a survey that friends of participants who were studying in various American universities took online (n=6). To protect the anonymity of the participants, especially considering the sensitivity of the topic of inquiry, the location of the non-research university, as well as the locations of the universities which online respondents attended, is not disclosed and is referred to as K. University. Furthermore, pseudonyms are used for all of the participants, friends, family members, faculty, and students.

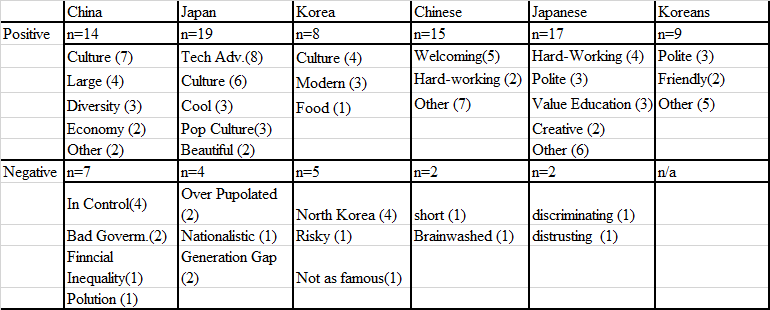

14Additionally, 33 open ended surveys were collected from local American students regarding the stereotypes of Asians, the predicted difficulties in Asian students’ adjustment to the U.S., and perceived ethnic differences in stereotypes of Chinese, Japanese, and Koreans. When examining the data, we looked at internal and external conflicts as well as general difficulties the young women had associated with their adjustment to the American higher education system and intercultural relationships. Particular attention was given to the difficulties due to the students’ cultural background and gender.

Results/Findings

15Out of the 20 interview participants, 13 have reported some form of discrimination or sexual harassment based on their gender or being Asian. One online survey participant reported being raped. Japanese female students reported the most discrimination based on their gender, and had the most severe encounters with sexual harassment compared to their Chinese and Korean cohorts. The most severe case was the online anonymous report of rape and no other information was provided; other cases of sexual harassment described in the interviews are described in more detail.

16 One such case was Saki, who had two very disturbing experiences within her first two months in the U.S. Saki came to the U.S. in January 2016 from Tokyo. She was raised by her single mother in Tokyo, and aspires to become a researcher in the future. She was very passionate about physics, but failed the exam to get into university in Japan. Instead of studying for a year and retaking the exams, she decided to study English and worked several part-time jobs to make money to study in the U.S. She was very concerned about not putting too much financial strain on her mother. When she arrived, she was looking forward to taking physics, but the class was already full, so she took astronomy. In her astronomy lecture class, in an auditorium of nearly one hundred students, one day an American boy sat next to her and inquired about where she was from. When Saki told him she was from Japan, his comments made her very uncomfortable.

17Saki: American guy asked me, “is Japanese really easy, you know, to have sex?” And I asked why he asked me and why he think so. He said some TV show or website, I don’t know. He said some Japanese girls always want to have sex with American, so he asked me if I wanted to... (she paused and looked down).

18A: He asked you if you want to have sex with American guy?

19S: Yeah… It is so mean, maybe he is a mean person, my other American friend said that guy is mean. We have a big lecture for Astronomy class and he sat down next to me and ask me weird things.

20A: So what did you tell him?

21S: I never replied him, I just don’t like that, I am not… you know... and I didn’t want to talk to him, so I see him, I don’t talk to him, and I changed seats.

22This, sadly, was not her only experience. When asked about any difficulties she was having in socially adjusting to the life in the U.S. she said:

23S: I am really not sure if this is normal. In Japan, guys are not so active or persistent, no, I mean, I don't know, but in the U.S. guys ask things that are (pause), you know, I am not sure how to explain it, but maybe not things you ask people who are like strangers. I mean we are not close…

24 A: What kind of things do they ask?

25S: Well, you know, if it is just, “Do you have a boyfriend?” that is still okay (pause), but even though we don't know each other I was asked “Are you still a virgin?” so I didn't know if that's normal so I asked my American roommate. I told her, “In Japan we would not ask this, but in America is it okay?” I mean, this guy wanted to play 21 questions, and I had to answer the truth, so I asked, “Is it normal to ask this in a game?” and my roommate said it was disgusting. Also, how American guys behave toward females, obviously because they are female. If between girls it maybe okay, but when a guy is suddenly overly friendly, it’s kind of uncomfortable. Now, I became more wary of such attention. I think they think because I am Japanese I am open and easy to have sex with. I am thinking, ”What the guys are thinking?” now when I interact with guys. In Japan, we are conscious of not creating a bad atmosphere; we don't want to be hated. And I really wanted to interact with Americans, because it really improves my English and I can learn so much. Like, recently I learned LOL.

26On our way home from the interview Saki remembered another question that she was asked about Japanese high school girls. An American guy asked to see her high school picture and commented on that he heard the skirts in Japanese high schools were very short. Furthermore, Saki was not the only one who was asked if she was a virgin, and was confused if this was an American norm. Another female Japanese student was asked on the bus by a classmate if she was a virgin, and they were not playing a game. She also had the same reaction. During the interview she asked if it was normal or not and if it is common in the U.S. She said she was not sure if she should get mad, or had to answer. She later also consulted her friends if it was normal behavior or not.

27 Talking with another Japanese female students from Tokyo, she was also confronted with some American guys that were aggressive in their sexual pursuit. She commented that she was more popular in this rural area compared to when she lived in California, so perhaps she said, “Asian girls being rare in rural areas and that’s why we were popular”. She also mentioned that it could be due to the popularity of anime culture, and reflected that it could be partially because, in Japanese culture, it's hard to say no, so Japanese girls pretend to be nice, and it was hard for her to get away from this guy. Another Japanese student explained it as:

"I think in Japan people get to know each other well, then have sex, but Americans want to do it right away. I once told a guy, 'I don't want to do it because I barely know you,' and he said, 'There is a good way to get to know each other more.’ It's like, if we don't do it, then we can't get to know each other. It's like sex is tool to get to know each other. In Japan they are not like that."

28Another issue concerning gender as well as ethnicity was reported by Mina. “Americans often talk to us like we are children, that Asian females look very young and they think are 5 years younger than what we really are. This is especially true for me and other Asian girls here.” Mina’s friend also mentioned that she sometimes was treated like a kid in the U.S. Saki, for example, found math easy, and it was mentioned by a few students that Americans are under the impression that Asians are good at math, as only during math classes do American students approach Asian students with questions.

29The results demonstrated that the harassment and gender-based discrimination was reported more by Japanese females, while Chinese and Korean female students reported mostly discrimination and prejudice based on their ethnicity. The only student who wasn’t a Japanese female was Ho, a Korean student who commented on this issue: “Some guys [American] just come and, like, how do I say, like put their hands around you, and woohoo. This is, like, wrong." Other Chinese and Korean students did mention that sometimes American guys are more direct, but they had no difficulty in stopping this unwanted attention, and were not very concerned with this issue. Another problem that East Asian students were uncomfortable with was with their roommates’ boyfriends sleeping over in the room. East Asian students reported the line between friendship and romantic relationship very hard to distinguish compared to the situation in their home countries. One student from Taiwan was dating an American for 6 months when he, to her surprise, asked her to become his girlfriend. She responded with, “What have I been for the last 6 months?” Many students also reported more physical contact between sexes, and ambiguous sexual relationships as a culture shock. One student reported in an online survey, “My roommate often stayed with a boy in our room, so I thought he is her boyfriend. But actually, he wasn't. Then I thought the relationships in the U.S. are closer than Japan.”

30 On the question of prejudice and discrimination, students reported various experiences. The largest category that emerged was discriminations in the classroom, both from other students and professors. Two students felt discriminated against by professors and five students felt that American students displayed an obvious prejudice against them through various actions, such as ignoring the East Asian student, not acknowledging their presence, or disregarding their opinions because they were foreign.

Discrimination from Professors

31 The two instances of discrimination felt from professors both took place in classrooms after class. These two cases were brought up during the interviews when the students were asked about any discrimination they experienced in the U.S. The first case emerged from good intentions of the professor, but a Japanese student, Nana, felt somewhat discriminated against, though admitted that the professor was trying to be helpful. The professor approached her and told her that he had a Japanese student in his class last year, and he knew that Nana would struggle with the content of his class due to her English ability, so he offered to send her the power point slides of all the lectures that were not available to other students. Nana said the class was not that hard, and she was not struggling with the content, but extra help doesn't hurt. However, she was a bit offended by the idea that only because one Japanese student found this class challenging, the professor was convinced that it would be difficult for Nana as well. In her tone she expressed some frustration, and she felt as if she was looked down upon without a valid reason. The second case was more traumatic and occurred after a math lecture to Ikumi:

For me, it was one of my professors (who was racist). I did the math homework, but the professor didn’t hear me out, just said, “I don’t take late work.” So I said I don’t need the points for the assignment, just want to know if the answers I wrote were right, and asked him to just check it. He just said “No! No!” and kept repeating it. I almost started to cry because he was so cold. It was right before the exam, and I needed to know the right answers from this assignment to study for the exam.

32Ikumi struggled with math, and found it to be the most challenging subject. She particularly struggled with the vocabulary and the overall test and assignment were both very challenging for her.

Discrimination from American Students as Asian Students See it

33The common prejudice was that American students believed that Asians cannot speak English. In class, discussion, or group work, American students would walk past Asian students and not form groups with them, avoiding eye contact. Other forms of discrimination occurred outside the school, including on the bus, in the bank, on the street, etc. The instance on the bus was an experience described by Saki:

"Sometimes, like last week, I went shopping with a Chinese friend and on the bus, when talked to by a guy, an older guy approached us and he pointed to Li and said, “Are you Korean?” So we said, “No, why do you think so?” He said, “I know how to identify Korean, Chinese, and Japanese apart. Japanese have down eyes, Korean have straight, and Chinese have upper eyes.” He pointed to another friend and said,”You totally look Chinese, you look…” so on. He didn’t point at me, but when I said I was Japanese he said “I don’t think so, but sometimes my opinion is not correct, but most of the time I can identify them.” Maybe he did not think its wrong, and maybe it is kind of… discrimination, maybe, but I felt bad thing from this, not so good, not so..."

34Saki was uncertain if this was a kind of discrimination, but it was certain she felt very uncomfortable, especially with her national identity being questioned. Other forms of discrimination, both direct and indirect, were reported. Being approached when in a group with other Asian students and having derogatory terms directed at them was another form of racism, as well as being referred to as a “Jap.” Another Japanese student, through the online survey, who was studying in urban Illinois reported being insulted on the train. There were also positive attributes prescribed to Asian students.

“Americans think Asians are good at math. They also do not know where Malaysia is. Sometimes then we explain it’s between Thailand and Singapore. They still do not know. They really don't understand that we can be ethnically Chinese and live in Malaysia.”

35Many Americans cannot tell the difference between people from different Asian countries. Other students also reported that Americans believe that Asian students study hard, and are good at math, but bad at English. One Chinese student felt that Americans had a dislike toward China. When she said she was from China, she had a feeling that the American students were put back by this. Another student from Taiwan said, “Americans seem to be not familiar with foreign cultures, or they are just not much interested. Some locals have never met Chinese people before.”

American Students' Opinions

36A survey of American students’ opinions on East Asian countries and people yielded interesting results. The students were asked about their own opinions, as well as about the opinions of an average American. They showed that Japan was viewed most positively, followed by China, then Korea. Korea was the least famous and understood, with the largest number of students indicating either no interest in the country or not knowing anything about Korea or Korean people. Overall, there were more positive impressions of East Asian countries and people in personal opinions of the students (Table 1). However, when the students were asked about the image of people from East Asian countries that an average American holds, the results were inconsistent, with the “model minority” having more negative responses (n=12) identified than positive (n=9). The positive responses were more homogeneous, with the most common responses being ‘smart’ and ‘hard-working.’ The negative responses were much more diverse: bad at English, prude, standoffish, workaholics, they don't like Americans, foreign, and so on. Another theme that emerged was not the stereotype of Asians, but pertaining to the views on Americans. Seven responses of how Americans view Asians indicated that the average American view was limited or biased. The top categories were American views are biased, Americans are racist, and Americans only know the stereotypes of “dragons and ninjas,” or every Asian is a Chinese. One American student responded, “Honestly, we are racist bastards.” (S#15). American students seem to be aware of the discrimination and limited knowledge of an average American concerning people from East Asia.

Table 1: Local Students Impression of East Asian Countries and People

37The most interesting result is that these surveys provided additional proof, on top of the testimonies of East Asian students, that many Americans had little knowledge and interest in Asian countries and knew few things about the people. One 23-year-old female American student wrote, “Americans are ignorant of East Asian countries so they may not be able to differentiate the various countries or cultures.” (AM Survey#27). Surprisingly, the American students were able to correctly identify what Asian students might be struggling with in the U.S. without even having interacted with any Asian students, such as the identified language barriers, racism, and difficulty in fitting in. Interestingly, one 19-year-old American female, majoring in Advertising, wrote that the challenges of East Asian students’ interactions with American students are, “East Asian students tend to stick together, so it can be hard to approach them.” (AM Survey#23). So the American students’ expectation of language being a problem, and Asian students not speaking English, contributes to local students not initiating conversation. While American students may have an interest in Asian cultures, they find it hard to approach a group of students who are exclusively from Asia.

Discussion

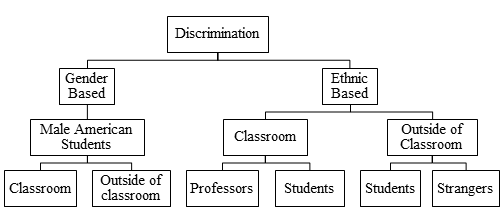

38Discrimination was noted in numerous studies to negatively affect the process of cultural adaptation for international students (Nora & Cabrera, 1996; Hwang & Goto, 2009). Wang and Cooper (2010) noted that ethnic stereotypes are more evident for males, while for ethnic females, gender stereotypes become more conspicuous. The authors noted, “The stereotypes of Asians that Americans may have are mostly about Asian males and accordingly represented through male Asian models in media portrayals.” (Wang & Cooper-Chen, 2010, p. 85). To sum up the results, with regards to discrimination, sexual harassment was the most common category, followed by racism and positive stereotypes.

Figure 1: Summary of the nature, location, and participants of prejudice activity

39The troubling emergent theme is that, when confronted with uncomfortable situations, the Japanese girls are ambivalent, confronted with the desire to fit in and obliged by the norms of the American society, yet at the same time are made to feel extremely uncomfortable and not sure if this is a norm in the U.S. The position of being a foreigner makes these young women very vulnerable, and as Saki described, in Japanese society, not offending anyone and preserving harmony is very important as the Japanese are afraid of being disliked or excluded from the group. The question of virginity has no right answer as it is related to what Tolman et al (2005) referred to as the “slut/prude” tightrope. If the answer is yes, the woman might be viewed as a “prude”, and if the answer is no, she could be viewed as a “slut”. On the internet discussion forums, young American females are often at a loss on how to answer such a question, especially when coming from someone who they are not in a relationship with, however there is a general consensus that it is inappropriate. For Japanese females, this problem is tripled. Besides the regular dissonance that the American females experience, the other two factors are the problem of being a sojourner who does not know the social norms of America - thus not knowing how appropriate it is - and further, the influence of Japanese culture and their own cultural identity. According to Tanaka (1993), Japanese are likely to define themselves by comparing themselves to others similar to them. Furthermore, Japanese students are usually less sexually active than their American cohort (Ito & Morales, 2003). Japanese were also noted to pay attention more to context than Americans, and the inability to fully comprehend the situation such as this one made it difficult for them to judge the appropriateness of the behavior of the male students. The various differences in self-perceptions between Japanese and Americans was also noted by Cousins (1989) and unique patterns of communication among the Japanese (Doi, 1973) could serve as possible explanations to the differences that were observed.

40Online forums of young Americans suggested the question of “Are you a virgin?” is not uncommon, but Americans knowing the inappropriateness of the behavior toward them are able to come up with witty responses such as “Why, are you trying to start a club?”[1], “Why, you planning a sacrifice ritual?” or “No, life screws everyone over”[2]. For Japanese students the importance of their cultural values prevents them from producing such responses. In Japanese culture, the importance of the atmosphere and relationships between people is a top priority, and offending or disagreeing with another person will damage that relationship. Furthermore, international students find themselves playing the role of a representative of their home country in the eyes of the local populace (Ito & Morales, 2003), which put an additional pressure on them to behave appropriately.

Conclusion

41 This study explored both ethnic and gender stereotypes of Asian female students, finding that gender stereotypes affected Japanese female students to a higher degree than their Chinese and Korean cohorts. Furthermore, Japanese female students had the most difficulties in their interactions with American males, describing them as more aggressive than Japanese males. Ethnic discrimination was experienced regardless of country of origin. The results of the survey of the American students suggest that this may be due to the Americans’ limited knowledge of the differences between Asian countries and the common stereotype of Asians being collective. Conversely, the perceived stereotype of a “Japanese Woman” might be somewhat different than the stereotype of Korean or Chinese. It would be highly beneficial for future studies to explore the differences between the images of Japanese, Chinese, and Korean women in the U.S., if such a difference is, in fact, existent.

42Based on these findings, East Asian female sojourners are subjected to various forms of discrimination and harassment during their studies in the U.S. Physical and mental health are damaged beyond the acculturation stress as they are subjected to harassment and discrimination. The main purpose of student sojourners is to study, and universities are responsible for providing an environment that would enable international students to receive the education they are paying for; however, this is very difficult, if not impossible, to do in a hostile environment. During orientations, universities must provide two kinds of training. First of all, the students must be accustomed to what is appropriate and inappropriate behavior, what constitutes harassment, and what to do in those situations. This kind of training is provided to the faculty to limit the liability of the university, but is not offered or mandatory to the students. Secondly, higher education institutions need to educate the students about social norms, self-protection, and how to deal with dangerous or uncomfortable situations outside of the university.

43The broad discourses that have brought to light by this research are the disadvantages and challenges faced by Asian women while studying in the United States that are based on their own culture. In particular, the general Asian stereotypes as well as negative stereotypes of Asian women in the U.S. make adjustment to studying abroad a grave disadvantage for Asian women. While they try to understand the social norms of American culture, it is a process that requires a lot of time and effort. The challenges of studying abroad are numerous and hard to overcome, and the experiences they had of sexual harassment make them wary of future interactions with American males. Often, Asian students retreat into their own group where they feel safe. It was commonly observed that when attending a social event, Asian female students would never do so alone, and instead would only attend an event as a group.

44 The suggestion for Japanese students is to take extra training in a direct way of communication. The shyness of Japanese female students can be misinterpreted as interest. If a direct 'no' is not given, it is not uncommon for American males to increase their efforts in their pursuits. For the purpose of self-defense, Japanese females are advised to learn a few lines that are direct and could be used toward the unwanted attention they are receiving. However, this does not address the underlining problem of the lack of cultural empathy among the students, professors and local population in the U.S. Perhaps, if the problem is this severe among the educated and in higher institutions, other levels of our society are even more severely affected? How many cases of sexual harassment in rural or urban higher institutions go unreported? The Japanese female students in their reports to their home institutions only reported the positive experiences in the U.S. and reflected critically on themselves, a primal example from the East to the West.

Bibliographie

Akuto, H. (1994). International understanding, international misunderstanding, and the communication gap. Creating Images: American and Japanese Television News Coverage of the Other, The Executive Committee for a Comparative Study of United States and Japanese Television News Coverage. The Mansfield Center for Pacific Affairs.

Barratt, M. F., & Huba, M. E. (1996). Factors related to international undergraduate student adjustment in an American community. College Student Journal.

Berry, J. W., & Kalin, R. (1979). Reciprocity of inter-ethnic attitudes in a multicultural society. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 3(1), 99-111.

Berry, J. W. (2009). A critique of critical acculturation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 33(5), 361-371.

Bochner, S., Furnham, A., & Ward, C. (2001). The psychology of culture shock. East Sussex: Routledge.

Bonazzo, C., & Wong, Y. (2007). Japanese international female students' experience of discrimination, prejudice, and stereotypes. College Student Journal, 41(3), 631.

Cheng, D., Leong, F., & Geist, R. (1993). Cultural differences in psychological distress between Asian and Caucasian American college students. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 21(3), 182-190.

Cousins, S. (1989). Culture and self-perception in Japan and the United States. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(1), 124.

Doi, L. (1973). The Japanese patterns of communication and the concept of amae. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 59(2), 180-185.

Fletcher, J., & Stren, R. (1989). Language skills and adaptation: A study of foreign students in a Canadian university. Curriculum Inquiry, 19(3), 293-308.

Frith, K., Cheng, H., & Shaw, P. (2004). Race and beauty: A comparison of Asian and Western models in women's magazine advertisements. Sex Roles, 50(1-2), 53-61.

Fritz, M. V., Chin, D., & DeMarinis, V. (2008). Stressors, anxiety, acculturation and adjustment among international and North American students. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 32(3), 244-259.

Furnham, A., & Bochner, S. (1986). Culture shock : Psychological reactions to unfamiliar environments. London: New York: Methuen.

Furnham, A. (1993). Communicating in foreign lands: The cause, consequences and cures of culture shock. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 6(1), 91-109.

Gyory, A. (1998). Closing the gate: Race, politics, and the Chinese Exclusion Act. University of North Carolina Press.

Hama, T., & Plutchik, R. (1975). Personality profiles of Japanese college students: A normative study. Japanese Psychological Research, 17(3), 141-146.

Harris, R. (1999). A cognitive psychology of mass communication (3rd ed. ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Hoppenstand, G. (1992). Yellow devil doctors and opium dens: The yellow peril stereotype in mass media entertainment. In Popular culture: An introductory text.

Hsu, C. (2011). Factors Influencing International Students' Academic and Sociocultural Transition in an Increasingly Globalized Society. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses.

Hwang, D. (1986). M. Butterfly. New York: Plume, Penguin Books.

Hwang, W., & Goto, S. (2009). The impact of perceived racial discrimination on the mental health of Asian American and Latino college students. Asian American Journal of Psychology, S(1), 15-28.

Ishii, K., Kaigo, M., Tkach-Kawasaki, L., & Hommadova, A. (2015). American attitudes toward east Asian countries. Journal of International and Advanced Japanese Studies, 7, 111-120.

Ito, K., & Morales, E. (2003). Cross -cultural Adjustment of Japanese International Students in the United States: A Qualitative Study. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses.

Kearney, D., & Knight, H. (1878, February 28). Appeal from California. The Chinese Invasion. Workingmen’s Address. Indianapolis Times.

Kim, S. (2006). Academic oral communication needs of East Asian international graduate students in non-science and non-engineering fields. English for Specific Purposes, 25(4), 479-489.

Kim, Y. Y. (2001). Becoming intercultural: An integrative theory of communication and cross-cultural adaptation. Sage.

Lee, D., Kang, S., & Yum, S. (2005). A qualitative assessment of personal and academic stressors among Korean college students: An exploratory study. College Student Journal, 39(3), 442.

Lee, S. (1996). Unraveling the “model minority” stereotype: Listening to Asian American youth. New York: Teachers College.

Nora, A., & Cabrera, A. (1996). The role of perceptions of prejudice and discrimination on the adjustment of minority students to college. The Journal of Higher Education, 119-148.

Oberg, K. (1960). Cultural shock: Adjustment to new cultural environments. Practical anthropology, 7(4), 177-182.

Perrucci, R., & Hu, H. (1995). Satisfaction with social and educational experiences among international graduate students. Research in Higher Education, 36(4), 491-508.

Poyrazli, S., Kavanaugh, P. R., Baker, A., & Al‐Timimi, N. (2004). Social support and demographic correlates of acculturative stress in international students. Journal of College Counseling, 7(1), 73-82.

Prasso, S. (2005). 'Race-ism,' Fetish, and Fever. In The Asian Mystique. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Books. 132-164

Redmond, M. V., & Bunyi, J. M. (1993). The relationship of intercultural communication competence with stress and the handling of stress as reported by international students. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 17(2), 235-254.

Rose-Redwood, C. (2010). The challenge of fostering cross-cultural interactions: a case study of international graduate students' perceptions of diversity initiatives. College Student Journal, 44(2), 389.

Ruiz, E. (2009). Discriminate Or Diversify. Lothian, MD: PositivePsyche. Biz Corp.

Seagrave, S., & Seagrave, P. (1993). Dragon lady: The life and legend of the last empress of China. Vintage.

Sharp, G. (2010). The Submissive Asian Stereotype: Classy Asian Ladies Dating Site (3 March, 2010). Retrieved October 10, 2016 from https://thesocietypages.org/socimages/2010/03/03/the-submissive-asian-stereotype-classy-asian-ladies-dating-site/

Siy, J., & Cheryan, S. (2013). When compliments fail to flatter: American individualism and responses to positive stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(1), 87.

Smedley, B., Myers, H., & Harrell, S. (1993). Minority-status stresses and the college adjustment of ethnic minority freshmen. Journal of Higher Education, 434-452.

Song, Y., & Moon, A. (1998). Korean American women: From tradition to modern feminism. Greenwood Publishing Group.

Swagler, M., & Ellis, M. (2003). Crossing the distance: Adjustment of Taiwanese graduate students in the United States. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 50(4), 420.

Taylor, C. R., Lee, J. Y., & Stern, B. B. (1995). Portrayals of African, Hispanic, and Asian Americans in magazine advertising. American Behavioral Scientist, 38(4), 608-621.

Taylor, C., & Stern, B. (1997). Asian-Americans: Television advertising and the “model minority” stereotype. Journal of advertising, 26(2), 47-61.

Tolman, D., Hirschman, C., & Impett, E. (2005). There is more to the story: The place of qualitative research on female adolescent sexuality in policy making. Sexuality Research & Social Policy, 2(4), 4-17.

Trice, A. (2004). Mixing it up: International graduate students' social interactions with American students. Journal of College Student Development, 45(6), 671-687.

Uchida, A. (1998, April). The orientalization of Asian women in America. Women's Studies International Forum, 21(2), 161-174.

Van Der Zee, K., & Van Oudenhoven, J. (2000). The Multicultural Personality Questionnaire: A multidimensional instrument of multicultural effectiveness. European journal of personality, 14(4), 291-309.

Wang, X., & Cooper-Chen, A. (2010). Gendered Stereotypes of Asians Portrayed on the Websites of US Higher Education Institutions. Visual Communication Quarterly, 17(2), 77-90.

Wong, M. (1980). Model Students? Teachers' Perceptions and Expectations of Their Asian and White Students. Sociology of Education, 53(4), 236-246.

Wu , F. H. ( 2002 ). Yellow: Race in America beyond black and white . New York : Basic Books .

Zhang, J., & Goodson, P. (2011). Predictors of international students’ psychosocial adjustment to life in the United States: A systematic review. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35(2), 139-162.

Zhou, Y., Frey, C., & Bang, H. (2011). Understanding of international graduate students’ academic adaptation to a U. S. Graduate School. International Education, 41(1), 76-84.

Pour citer ce document

Ce(tte) uvre est mise à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International.