Decentering State Propaganda in Zimbabwe; Persuasive Strategies in Movement for Democratic Change’s (MDC) Television-Electoral Advertisements.

Résumé

Les médias d'État et la ZANU PF ont qualifié le Mouvement pour le changement démocratique (MDC) de front occidental. Cet article examine la manière dont le MDC a contré la balise «sell out» à travers ses publicités télévisées électorales de 2008. Il propose une synthèse de la théorie qui englobe la démocratie, la postcolonialité, la publicité, la propagande et la sémiotique à l'étude des annonces électorales du MDC. L'approche peut produire des données plus récentes et plus riches sur la publicité politique, la communication politique et les discours sur la démocratie dans le Zimbabwe après 2000.

Abstract

The state media and ZANU PF have branded the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) as a Western front, eschewed in ideology whose sole mission is to reverse the gains of the country's hard-won independence. This study investigates how the MDC countered the 'sell outs' tag through its 2008 television-election adverts. The paper proposes a synthesis of a theory that encompasses democracy, post-coloniality, advertising, propaganda, and semiotics to the study of the MDC's election advertisements. The approach may yield newer and richer data on political advertising, political communication, and democracy discourses in post-2000 Zimbabwe.

Table des matières

Texte intégral

Introduction

1Political advertising can be defined as a “piece of communication, using a range of media, designed to garner positive feelings towards the sponsors (Lilleker 2006). Propaganda can thus be defined as referring ”solely to the control of opinion by significant symbols, images, stories, rumors, reports, and other forms of communication“ (Severin and Tankard 2001: 109). It mainly involves the manipulation of representations and these representations may take pictorial, written, or musical form (Severin and Tankard 2001). In this research, the MDC's political adverts are analyzed precisely as political art and communication. The study is concerned with deconstructing and identifying persuasive strategies and persuasive devices (glittering generalities, value transfer, bandwagon, name-calling, selective information, and so forth) nearly all of which are commonplace in commercial and political advertising (Scammell and Langer 2006: 24). Propaganda and persuasion are seen as identical; ”it is perceived that only when an act benefits the source, but not the receiver, can such an act be perceived as propaganda“ (Severin and Tankard 2001: 109).

2Electoral propaganda articulates in the same terms as advertising propaganda, it aims to make an impact on the audience to get their vote in a given campaign. That is, ”in essence political propaganda is no different from advertising, the latter concept presupposes to make something known, advertise it, a way of propagating it to stimulate demand of goods and services“ (Corona, 2011, p. 326). Electoral propaganda aims at making a given candidate known, or even a party that has been recently created seeking to position itself. It does not intend to just inform using data or proposals, but rather to convince through emotions. According to Corona (2011):

Targeting the masses, political propaganda intends to exert its influence with emotive effects and not through reasons. Exaggerating the candidates' qualities and concealing their defects, just like it would happen with products. Political propaganda, made by skilled specialists and foreign advisors, intends to interpret and answer surveys, study different aspects of electoral behavior, to offer the people what they want to hear (p. 326).

3Consequently, they make use of a series of persuasion strategies, some of which are more effective than others, since they allow positioning the product (Candidate and party) better. These strategies appear in the parts of the discourse and the way they are presented. Studying them allows not only understanding how persuasive messages articulate but also explaining the relation between these propaganda communicative processes and the meanings they are likely to generate on the targeted audience.

4The use of propaganda in Zimbabwe's politics dates back to the colonial era where it was used by the colonizers as a form of maintaining political hegemony over Africans (Chikonzo 2005). Over the years, propaganda has been a constant feature during electoral times where it has been used by the ZANU PF party to outmaneuver the opposition. Thus, in a young liberal democracy such as the MDC it is vitally important that the political advertisements on television benefit not only the political party but to a large extent the citizens as well, by creating a well-informed citizenry. Having been in existence for the past two decades, the MDC is the only political party to subject the ruling party ZANU PF to continuous and consistent contestation and even defeat in the 2008 general election. To this end, the MDC deserves critical attention because unlike other political parties it has caused serious ructions on the ruling party.

5Ochoa (2000) observes that political communication is made up of six areas of interest: public opinion, the analysis of the content of messages, political-social behavior, the leadership of power groups, the effects of political communication, and political propaganda. This study is placed in the latter, and more specifically, within electoral propaganda. This is the one generated during the 2008 harmonized elections, one of the periods with the greatest propaganda production in Zimbabwe (Orgerek; 1998, Chuma; 2004, Moyo; 2005, Masuku; 2011, Mano; 1997, Mukasa; 2003, Moyo; 2005, Muwonwa: 2011, Mboti; 2010, Chuma; 2004 and Moyo 2005)). The study concedes that in democratic systems, communicative processes aimed at persuading must be subjected to continuous questioning because they are based on the relations between citizens and politicians, this relationship in turn is the essence of democracy. The research, therefore, does not romanticize or glorify the MDC, but subjects its propaganda texts to critical analysis.

6Political advertising has been a subject studied by a vast majority of scholars in several aspects such as issues versus images (Gross et al 2001), negative advertising (Pinkleton, 1997), video style (Kaid and Johnston, 2001), and electoral effects (Goldstein and Freedman, 2002). Surprisingly, all these components, until now, have not been explored in the light of another catalyzing aspect such as the system where they find their best use, democracy itself. Thus, this study also investigates the democratic intent of the adverts and the possible factors militating against such intentions that may be embedded in the techniques used in the texts under study.

7The research is grounded in the light of emerging and established democracies (Esser and Pfetsch, 2004; Voltmer, 2006), a perspective which scholars of political advertising in Zimbabwe have largely ignored. Therefore, an analysis of MDC election adverts is expected to stimulate a new area of research filling the perceived gap mentioned. This would lead to scientific expectations and theoretical frameworks for the effect of democracy as a system in the way how politicians shape their messages through audiovisual texts. The research analyses four televised MDC adverts from 2008 harmonized elections namely; Morgan Jobs, MDC Team, let us make Zimbabwe Great again and Oldest president in history?. The research is guided by three objectives, Firstly it seeks to explore how MDC's counter-propaganda strategies affirm, perpetuate, question, and/or negate state propaganda narratives. Secondly, it Unveils the consistencies and contradictions in the counter-propaganda narratives and lastly, it analyzes how the counter-hegemonic strategies could have undermined the democratic intentions of the MDC.

8The adverts are analyzed through an eclectic range of theories and methodologies. Concepts such as Negative and Positive advertising, Propaganda techniques, and Mbembe's postulations-On the post colony is employed in the quest to understand the persuasive strategies that the opposition used to counter state propaganda narratives. Thematic analysis, visual analysis, semiotic analysis, and multimodal discourse analysis are used in the analysis of MDC propaganda texts. The advertisements are part of the 'system of signs' of post-colonial Zimbabwe designed to maintain or to challenge the hegemony of the ZANU PF elite. The proposed new analysis should focus on, the signs, vocabulary, and narratives produced (Mbembe, 2001, p. 103), understanding MDCs advertisements are arguably part of what Chipkin (2007) calls the vulgar reproduction of sovereignty in the 'absence of state power'. In doing this, the study holds that election advertisements should be regarded as tools of political communication.

Name calling; Oldest president in history?

9Name calling is a propaganda tactic in which negatively charged names are hurled against the opposing side or competitor. By using such names, propagandists try to arouse feelings of mistrust, fear and hate in their audiences. According to the Institute for propaganda analysis (1938) name calling as a propaganda technique, pushes the audience into accepting a 'fact' without any detailed consideration of context and other factors surrounding the issues raised by an advertisement. This name calling does not accord subaltern citizens the ability to design, modify, implement and lead, at an intellectual level considering its indulgence with words and images that lack the critical depth of their struggles. It is used when a candidate is trying to attack his/her opponent and degrades him/her through the use of insulting words and/or comparing him/her with other politicians or well-known people.

10March 29, 2008, harmonized elections were very much about personalities as much as they were about change Chibuwe (2013). Conventional wisdom then was a resolution of the country's crisis was predicated on the departure of President Robert Gabriel Mugabe from office. For Mugabe was perceived by the MDC advertisements as the sole author of the country's crisis and therefore his defeat would be a panacea to the country's economic and political problems. Inevitably. President Mugabe became the single most enduring focal point of the MDC election campaign. The obsession with personalities and negativity by the MDC election adverts during the run-up to the March 29, 2008 elections meant that more attention was given to name calling, squabbles, divisions, factional fights, and other controversies with little attention being given to the economic crisis. The MDC mainly emphasized President Robert Mugabe's old age as evidence that he was no longer fit to hold political office, while MDC's Tsvangirai was presented as symbolizing generational change. On the issue of Mugabe's age, the MDC in one of its advertisements presented an impression that voting for Mugabe at the age of 84 was the same as voting for old thinking. The advertisement asked the rhetorical question:

11”The oldest president in history?“

12(Old President advert 2008)

13The narrative went on to say that if Mugabe was elected he would be the oldest man in history to be sworn in for a six-year presidential term. The message ends by saying

14This election is your chance to vote for new ideas instead of old thinking. It's your chance to vote for the MDC and its leader Morgan Tsvangirai. (Old President advert 2008)

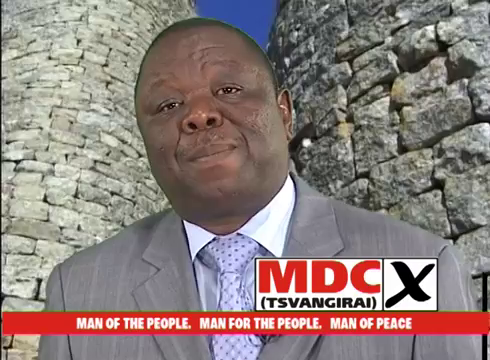

Figure 1 Old President advert (2008).

15Name calling goes hand in hand with Negative political advertising, also known more colloquially as mudslinging involves an aggressive, one-sided assault designed to draw attention to the opposition party's and/or candidate's weaknesses in either position or character (Kangira 2005). In this type of advertising, in general, the elements of criticism remain at the forefront (Balci, 2006). Negative political advertising which contains messages with ironic or sarcastic content explicitly or impliedly generally highlights inconsistencies in the promises made by the opponents or holds opponent candidates up to ridicule for involuntary or uncontrollable movements such as age, disability, and speech defects or criticizes personal lives of opponents (Inal & Karabag, 2010, p. 43). The advert (figure 1) suggests that if elected to the presidency at 84, Mugabe would be incompetent to run the affairs of government. It suggested other people would be doing the day-to-day business of governing the country. Mugabe's envisaged ineptitude is implied in figure 1. This method is intended to provoke conclusions about a matter apart from a partial examination of facts. From the advert, name calling can be viewed as a substitute for rational, fact-based arguments against the idea, or belief on its own merits.

16Amongst the emotions, negative political advertisements elicit are greater degrees or more intense feelings of disgust, anger, anxiety, and/or hatred, and lesser degrees or intense feelings of enthusiasm, hope, and/or pride (Stevens 2012).Name calling and negative advertising serve to incite fears and arouse prejudices in the hearers. The intention being that the bad names will cause hearers to construct negative opinions about the group or set of beliefs or ideas that the propagandist would wish to denounce. In this regard, giving Robert Mugabe a bad label is meant to make viewers reject and condemn him without examining all the available evidence. In this case counter, propaganda works through, among others, what Deacon et al (2007) call re-lexicalization and over-lexicalization in which something or someone is renamed and situations in which certain words are continually repeated. It also works through de-limited appropriation and/or appropriation of discourse (Tomaselli, 1992; Mbembe, 2001). While negative political advertising is intended to have a persuasive effect, encouraging the voter to support the candidate/party ( Tsvangirai and MDC) doing the advertising, it can also have a backlash effect (where it has the reverse impact of that intended) for example, amongst voters who dislike negative political campaigning or where the content of the advertisement is seen to be excessive in tone ('mudslinging') or discredited (when the content is known or shown to be false and misleading).

17It has also been found that negative advertising and name calling that is based on 'vicious personal attacks' is more likely to backfire than negative advertising based on issues (Johnson-Cartee and Copeland 1991; Roddy and Garramone 1988). In other words, what these scholars are saying is that negative messages backlash or backfire on their sponsor. This is also supported by Roberts (1995: 180-181) who asserts direct attacks have the greatest potential for backlash, followed by the direct comparison. The implied comparison is found to be the least likely to create a backlash because the format encourages the audience to generate their arguments. On the same issue, Gronbeck and Miller (1994:9) say the subaltern's responses generally are drawn between positive and negative poles: at times, they react with hope to portrayals of a new world, and at other times, with fear and pessimism to negative portrayals of opponents. While it might have been compelling to persuade the electorate that Mugabe had ruled for too long and thus overstayed his welcome, no assurance obsessing with his age would convince the electorate that Tsvangirai was a better alternative. Whereas the MDC's argument was grounded on democracy, the interpretation of the advert rests purely with the audience and as demonstrated above it could go either way.

Plain Folks device; MDC team

18This research has so far demonstrated that the MDCs advertising discourse is primarily multimodal and creative. This is due to the producers having to find inventive ways of re-using the widespread range of audio and visual (multimodal) semiotic resources to capture novel meanings and to persuade its prospective voters into action. This study is thus attentive to the audiovisual narratives which are carried by the multimodal semiotic resources as 'signs' in the selected MDC's television advertisements. Using the Plain Folks device, politicians present themselves as part of the common folks (Institute of propaganda analysis: 1937). It is highly related to a discourse in which candidates use the right words that connect them with the audience. This is achieved through appropriate visuals and words. These words are populist and people feel a connection with their candidate. The MDC -Team advert is a classic example of a plain folk device. In the MDC team advert, Tsvangirai appears on screen with various backgrounds. One of the backgrounds has a dilapidated house with malnourished children. He addresses the viewers:

My fellow Zimbabweans. I know we have been through so much together. Now is the time for more. Now is the time to build and not break. Now is the time to make and not take. What do you see for your future? I see opportunities for jobs. I see the upliftment of the rural communities. I see investment. I see a prosperous economy I see the MDC. (MDC -Team advert 2008)

19The advert suggests that ZANU PF sought to divide the nation by harping on the country's colonial history, further claiming that because of Zanu PF's economic policies ”it costs more to live under this government than under the previous ones“. Part of the text read:

You cannot feed people with clenched fists. Fists don't create employment. The MDC Economic plan will create an open society for growth, investment, and fair wages that we can be proud of. Economic freedom is achievable when we fight for the economic good of Zimbabwe's people, not only its politics. (MDC -Team advert 2008)

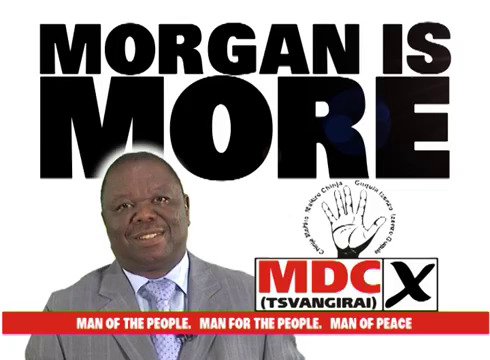

Figure 2: MDC -Team advert 2008

20The Team advert focuses on ZANU-PF's immersion in corruption, nepotism, regionalism, and ethnic chauvinism, stressing that the advent of independence in 1980 has left Zimbabweans at the mercy of ”a new network of repression, more formidable than the one under the colonial rule“ (Turok, 1987, p. 7). The background in figure 2 suggests that Tsvangirai fully understands what the subaltern are going through under the current regime. However, the composition of the picture suggests a different connotation. For example, his dressing compared to the image behind him projects a man who is well off trying, by all means, to fit into the subaltern narrative. Such imagery could be read as offensive to the plight of the suffering masses. The MDC used this approach to convince the audience that their presidential candidate, Morgan Tsvangirai is from humble origins, someone they can trust and who has their interests at heart. Propagandists have the speaker use ordinary language and mannerisms to reach the audience and identify with their point of view (Roddy and Garramone 1988). With Morgan Tsvangirai as its chief exponent, MDC electoral audiovisual narratives tear into the petit bourgeois inclinations of the ZANU-PF regime and its self-proclaimed identity as a people's regime. On the other hand, the suit and the red tie as seen in figure 2 also reproduces Morgan as a bourgeoisie. Morgan's choice of dressing seems to alienate him from the background, whilst he is dressed in an expensive suit, the ordinary folk in the background lack all the basics. Thus such a composition reproduces the same petit bourgeois inclinations that are associated with ZANU PF.

21During elections, ZANU-PF and MDC candidates have been presented as 'Teams' (Ncube 2014). It is important to associate notions such as 'team' with powerful controls that are meant to ensure that human bodies are disciplined and obedient in a certain way that guarantees team survival. Sport, and football, in particular, has been made use of as a 'political language,' a conduit for politically charged and robustly masculinized discourses, especially in post-2000 Zimbabwe (Sambo et al. 2013). Arguably, the resonance of this political aesthetic has a lot to do with the 'ordinary' people's affinity to sport and their 'popular knowledge' of the 'landscape' of sport. In this sense, the ability of sport, especially football to 'carry' sensual effects makes it useful to the political 'landscape' in general and issues of power and struggle in particular, especially in this case when the language of sport is very forceful ( Chiweshe, 2011; Mawere 2015; Ncube 2014). Taking into consideration ”the effects of fandom, for example, the violence and aggression, which may result from being a fan“ ( Chiweshe, 2011:174) and which characterize Zimbabwean soccer, it would be interesting to imagine a democratic party such as the MDC that adopts such characteristics.

22It is also important to mention the red cards and whistles as part of MDC symbols which have been raised during party rallies. Muponde & Muchemwa (2011) give reflections on how, during the colonial period, Africans used football stadiums as political 'fields' on which they 'performed' their disgruntlement through protest songs, symbols, and gestures deriding the colonial and racist regime. The whistle also became symbolic of the perceived ZANU-PF and Mugabe's rough play in managing the nation as well as during electoral participation. This rough play warrants not only a warning but total removal. In sports, a red card is a rare and harsh punishment symbolizing a player's total exclusion from the game. There is no room for negotiations and the decision cannot be revoked. Through the Team advert, the MDC has managed to problematize ZANU-PF's concept of the enemy as an outsider. It has also managed to play around on the space that has given ZANU-PF a claim to rule, which is the struggle space. However, the MDC has also appropriated 'going to fight' as the basis for heroism, thus the focus is on those who leave for war, those who are 'violent'. This simply becomes a displacement rather than a change. During one of his rallies, after the first round of the 2008 elections which he had won, Morgan Tsvangirai is said to have dismissed the possibility of winning a return leg after being defeated in one's home ground, further reflecting the relation between politics and sport (Mawere 2015).

23Sports metaphors invite team fans or members to see and 'act' themselves as extensions of their teams; hence they may invest a lot of emotions into them and be flexible to team 'discipline.' In line with the above, Noam Chomsky (1988) points to the sport as a major hegemonic instrument in the hands of elite classes. Ncube (2014) shares the same sentiments and pictures a contiguous relationship between sport and politics. This research argues that sport, like any other site of popular culture, is not a space monopolized by 'dominant' groups. Instead, it is a complicated space for both reproduction and subversion. The use of sports metaphors does not only give insights into the adversarial competition in Zimbabwean politics at the time but also demonstrates how politics and popular culture interconnect. Sports demand a lot of rigor and sheer determination, and for one to win they must demonstrate exceptional skills. Politics is often constructed as a game and like sports, it does not only demand strength and determination, but also a tactical skill for one to survive. The metaphors used in these adverts serve to show that politics in Zimbabwe has been characterized as ”bending the rules of the game“, intolerance, plots and sub-plots, political machinations, party splits, blame games, and political gamesmanship. In turn, through an understanding of the various techniques and the different rhetorical practices, one can better understand how such a political culture impacts political advertising techniques.

Transfer devices; Great Zimbabwe

24The transfer devices, also known as flag-waving, are linked with signs and symbols (Institute of propaganda analysis; 1937). Candidates use different symbols to make a connotation. These connotations could be positive or negative. It depends on the symbolsIn transfer, advertisers try to improve the image of a product by associating it with a symbol most people respect. . For example, in Slovakia, if a candidate uses 'hammer and sickle', the audience may link him/her with historical events and the old regime (Standler, 2005). On the other hand, candidates could use it as comparisons by showing that hammer and sickle are not positive, and people should not be afraid that the past would return (Standler, 2005, p.6). As previously stated, the MDC faced a crisis of legitimacy largely caused by the negative portrayal on state media. One of the major objectives of the MDC's advertisements was to validate its legitimacy as a viable alternative party. This was largely achieved through the appropriation of national symbols that had been previously associated with ZANU PF. In this advert Morgan Tsvangirai addresses the audience:

Hello, my fellow Zimbabweans. I know what you have been through. I understand the pain, the suffering and the disappointment. To make Zimbabwe great again (Great Zimbabwe monument appears on the background). (MDC Great Zimbabwe 2008)

25The significance of the 'Great Zimbabwe' monument in this advert is that Zimbabwe derives its name from the monument. Great Zimbabwe is a 'ruined' city in the south-eastern hills of Zimbabwe near Lake Mutirikwe and the town of Masvingo. It was the capital of the Kingdom of Zimbabwe during the country's Late Iron Age. Great Zimbabwe is believed to have served as a royal palace for the local monarch. As such, it would have been used as the seat of political power Garlake, P (1973). Among the edifice's most prominent features were its walls, some of which were over five meters high. They were constructed without mortar (dry stone). Eventually, the city was abandoned and fell into ruin. The Great Zimbabwe monument symbolizes power and authority and legitimacy (Ncube 2014; Mawere 2015; Sambo et al 2013). It is used by the ruling party ZANU Pf as part of its logo during elections to legitimize its historical entitlement to political hegemony (Figure 4). Thus associating the monument with the MDC is meant to shred off the sellout narrative peddled by ZANU PF and the state media which accused the opposition of being a Western front whose objective was to reverse the gains of the hard-won independence. Besides, the use of the Great Zimbabwe can be seen as a way of reclaiming national symbols and heritage that ZANU PF has monopolized.

26The advert presents a sign (the photographed image of Tsvangirai with Great Zimbabwe as a background) which itself signifies a concept 'Greatness'. This concept of greatness is what Barthes would describe as a mythic meaning. The mythic meaning of the advert connects the MDC, Great Zimbabwe, the past and present into one. However, such a crude composition may be misleading or temporary. Bignell (2002) believes that the photographic sign may be emptied of its meaning except in as much as it leads the viewer of the advert towards comprehending the myth.

Figure 3. MDC Great Zimbabwe 2008

Figure 4. ZANU PF logo

27According to Dyer (1986: 130), since ”denotation is not neutral or untouched by ideology, whatever image is being used some sort of meaning is attached that goes beyond the literal meaning“. On the connoted level because it is not neutral it is set within Zimbabwe, the advert cannot simply ”reflect ideology, it reworks it, thus producing new meanings“ and ”this connotation process depends on our knowledge of the forms of ideology that advertisements employ“ (Dyer, 1986 p. 129 -130). The term 'Great Zimbabwe', in this advert is made into a convenient keyword, based mainly on a deliberate Goebbels-like strategy of refrain and repetition. The MDC hopes that the prestige attached to the symbol (Great Zimbabwe) will carry over to the party's identity. However, such a proposition may have unintended consequences as observed by Mbembe (1992)

There is a sense in which the postcolonial state and citizen both claim the same space, idioms, and signs. Both appear to borrow and use the same sign-systems. In this relation, no one knows very clearly any longer what belongs to whom, or who has a right to what, still less who must be excluded and why (22)

28A further point can be made about this advert and that is how the color red has been used. It is no accident that the texts (MDC) and the background appear to have a red color. Walters et al. (1982) found a link between red and felt excitement. This is consistent with the generally accepted view that red is an exciting color (e.g., Guilford and Smith 1959; Tom et al. 1987). This feeling of excitement is pleasant and likely to lead to favorable attitudes. The background is simple, neutral color (Grey). Color may play a key role in the success of one advert and seems to be the first thing the audience will notice. Advertisers use color to reflect a specific brand, as well as attempt to communicate a certain mood dictated by the product itself. It shows the 'personality of a product that's often a lot harder to come up with. Colors and their underlying sociological and historical connotation certainly do produce specific reactions in particular contexts - emotions, associations, and even physical effects that can help advertisers in their quest for ever more accurate targeting. In this context, using proper color seems to be the quickest way to create a positive mood.

Bandwagoning; let's all vote for the change we can trust

29The Bandwagoning propaganda technique is a tool that is used mainly by marketers, where customers are doing it because others do it too (Institute of Propaganda Analysis 1937). It is used to convince the target audience that if they don't join in they will be left out. In the world of politics, especially during campaigns, phrases like ”everybody votes for“ or ”everyone supports“ are commonplace. Advertisers' pressure, ”Everyone's doing it. Why don't you?“ (Ferguson, 1997). This kind of propaganda often succeeds because many people have a deep desire not to be different (Institute of Propaganda Analysis 1937). Political adverts tell us to vote for the ”winning candidate.“ The advertisers know we tend to feel comfortable doing what others do; we want to be on the winning team. People are then expected to be a part of the majority because people often prefer to be a part of the majority rather than being different (Standler, 2005, p.6).

30In the let's all vote for the change we can trust 2008 advert, Tsvangirai appears on frame captured in a medium close up with the following lines:

My fellow Zimbabweans, I see your courage in the face of evil. I know that we are stronger than this evil and our victory is certain. Our new government will ensure that your suffering will come to an end and the rule of law will return and justice will be done. Political terrorism will have no place in our new government. I am a new President ready to deliver peace. (Voice-over) Let's all vote for the change we can trust. (Let's all vote for the change we can trust 2008)

31This device creates the impression of widespread support for the MDC despite its poor performance in rural areas. It reinforces the human desire to be on the winning side. It also plays on feelings of loneliness and isolation. This technique is used by the MDC to convince people not already on the bandwagon of 'change' to join in a mass movement while simultaneously reassuring that those on or partially on should stay aboard. The implication is that if you don't jump on the bandwagon of 'change' the parade will pass you by.

32Bandwagon propaganda goes hand in hand with Positive advertising, or so-called fair advertising, which seeks to create a positive effect/impact on voters. It is based on factual information about the candidate (Ferguson, 1997, p. 467-468). It should present the goals and objectives of the political agenda. It creates awareness and offers a positive effect on the sponsored candidate. Positive advertising is more about the message than about any comparison with others. It focuses on the sponsored candidate and its future impact on citizens and politics, it tells stories about him/her, presents his/her family and their background. However, there are surely always certain hidden issues, which are not featured in positive advertising since they would damage the candidate's positive effect.

33Asking would-be voters to choose between a bleak future (under ZANU PF) and bright prospects (led by the MDC government) is what Hugh Rank describes as ”positive propaganda“. Rank describes positive propaganda as the rhetoric of reformers, liberals who want to change or fix up parts of the existing system and replace it with a better one (Kangira 2005). Positive propaganda is the rhetoric of the Have-nots who seek to change the 'bad' (relief) and to get the 'good' (acquisition) 107. In the case of the 2008 presidential election campaign in Zimbabwe, Tsvangirai fits the above description perfectly. His band wagonning technique fits this description well. He enters the political arena as a 'redeemer'. The MDCs campaign propaganda can also be described as a rhetoric of ”dissatisfaction, discontent, and anger for not having the 'good', but it is also the propaganda of hopes, dreams, change, progress, and improvement.

Glittering generality; my name is Morgan you need more

34Using the glittering generality device, the MDC is focusing more on things or issues to which Zimbabweans are emotionally attached (Institute of Propaganda Analysis 1937). Using glittering generalities is the opposite of name calling. In this case, political parties surround their candidate with attractive and slippery words and phrases. They use vague terms that are difficult to define and that may have different meanings to different people. The MDC adverts make massive use of words like democracy, change, and jobs. Tsvangirai is trying to show how he is related to these topical issues. The candidate, by using the glittering generalities device, is pointing out these problems and presenting his or her ideal solutions (Hobbs and McGee, 2014, p.59). One of the payoff lines frequently used in the MDCs 2008 television adverts is:

35My name is Morgan. You need more and I need your vote…………

36This kind of language stirs positive feelings in people, feelings that may spill over to the party or the idea being pitched. As with name calling, the emotional response may overwhelm logic. Target audiences accept the candidate without thinking very much about what the glittering generalities mean or whether they even apply to their lived experiences. The adverts for politicians and political causes often use glittering generalities because such “buzz words” can influence votes. Election slogans include high-sounding but empty phrases like the following:

37Man of the people; Man for the people; Man of Peace

Figure 5. You need more 2008

38Using the glittering generalities propaganda technique, the MDC's campaign theme or slogan called for change, one of the widely used challenger's strategies in political campaign communication (Trent and Friedenberg 2000) The MDC slogan, “Chinja Maitiro” (Shona) / “Guqula Izenzo” (Ndebele), an exhortation to reframe one's political orientation, captured the party's commitment to running the country differently if elected to power. As a rallying call for change, the slogan encapsulated MDC visions of a new Zimbabwe that ZANU-PF stood accused of having failed to bring into existence since taking over from Ian Smith and the Rhodesia Front (RF) in 1980 (Gwekwerere and Mpondi 2018). The words and phrases seem vague and may suggest different things to different people but the implication is always favorable. Little, if any, the room is allowed for questioning such phrases. Indeed, all such images and words appear not only to go without saying but questioning them would almost attract the charge of heresy. On another level, the slogan offered a “cognitive shortcut” (Shea 1996:32) to the voters that when voting time came, they were going to vote for a change of government.

Conclusion

39Political advertising in Zimbabwe constitutes a form worth studying because, as the study has attempted to demonstrate, its content is often, if not always, set up and sorted to suit specific ways of seeing the world or gazes. A specific subtext seems to always be present behind every televised narrative. The argument, in essence, is that there is no way that political advertising can be a value-free or senderless medium. Rather, a critical understanding of the medium ought to involve recognizing its heavily selective, even ideological, nature. The implication is that politics and political advertising may polarize citizens, thereby undermining national unity and national-building. The winner takes all culture, exhibited in some of MDCs campaign advertisements means that political actors and their supporters will regard one another as enemies rather than encourage democracy and healthy competition, where people work towards the common good of the country. Political adverts, therefore risk being the new breeding ground for political intolerance, rather than terrains of reasoned engagement. Conflict exists between the principles of democracy and some of the adverts analyzed in this study. But this development between the democratic frameworks can be understood clearly if we look at it not from the level of principles but from that of the actual situation. If, so far, I have concluded that inside a democracy propaganda is normal and indispensable. On another level, the research however concedes that MDC electoral propaganda has also exceeded the tricks stage, simplistic procedures, techniques, and practices traditionally associated with ZANU PF, it has become multimodal and scientific.

Bibliographie

Balci, Ş. (2006). Negative political advertising in convincing message as fear attractiveness

strategy use (Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, Institute of Social Sciences, Selçuk University).

Chibuwe, a. (2013) A research agenda for political advertising in Africa: the case of Zimbabwe. Global media journal African edition 2013 vol 7(2):116-139

Chikonzo, K. (2005): 'The Construction of African Cultural Identities in Zimbabwean Films: From 1948 – 2000', M.Phil Dissertation, University of Zimbabwe, Harare.

Chipkin, I. (2007) Do South Africans exist? Nationalism, democracy and the identity of 'the

People'. Johannesburg: Wits University Press.

Chuma, W. (2008). Mediating the 2000 elections in Zimbabwe: Competing journalisms in a society at the crossroads. Ecquid Novi: African Journalism Studies, 29 (1), 21-41.

Chomsky N (1988) Language and Politics (ed. CP Otero). New York: Black Rose Publishing.

Corona, J. (2011). Propaganda electoral y propaganda política. Estudios de Derecho Electoral. Memoria del Congreso Iberoamericano de Derecho Electoral. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de

México.

Dyer, G. (1986). Advertising as Communication. London: Routledge.

Esser, F, & Pfetsch, B. (2004). Comparing political communication: Reorientations in a changing world. In F. Esser& B. Pfetsch, B (Eds.), Comparing Political Communication; Theories, Cases and Challanges (pp. 3-24). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ferguson, C. (1997) The Politics of Ethics and Elections: Can Negative Campaign

Advertising Be Regulated in Florida.Web. 21 April 2015.

GArlAke, P 1973 (1968) The Value of Imported Ceramics in Dating and Interpretation of the Rhodesian Iron Age. Journal of African History 9(1):13–33.

Goldstein, Kenneth, and Paul Freedman. 2002. “Campaign Advertisements and Voter Turnout: New Evidence for a Stimulation Effect.” Journal of Politics Vol. 64, No. 3: 721-740.

Gronbeck, B.E. and Miller, A.H. (1994). The Study of Presidential Campaigning: Yesterday's Campaigns and Today's Issues. In Arthur H. Miller and Bruce E. Gronbeck, (eds.), Presidential Campaigns and American Self Images. Oxford: Westview Press. pp. 3-11.

Gross, A. L., Gallo, T., Payne, J. G., Tsai, T. Wang, Y. C., Chang, C. C. & Hsieh, W. H. (2001). Issues, images, and strategies in 2000 international elections: Spain, Taiwan, and the Russian Federation. American Behavioral Scientist, 44 (12), 2410- 2434.

Guilford, J. P. & Smith, P. C. (1959). A system of color preferences. American Journal of

Psychology, 72(4), 487-502.

Gwekwerere T, Mutasa D, Mpondi D & Mubonderi B (2019) Patriotic narratives on national leadership in Zimbabwe: Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) and Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) song texts, ca 2000–2017, South African Journal of African Languages, 39:1, 56-66.

Institute for Propaganda Analysis records, 1937-1968. Manuscripts and Archives. Division Stephen A. Schwarzman Building Fifth Avenue at 42nd Street, New York

Kaid L L, Fernande J and Painter D (2001) “Effects of Political Advertising in the 2008

Presidential Campaign” 55(4) American Behavioral Scientist 437 - 456

Kangira J. (2005) A study of the rhetoric of the 2002 presidential election campaign in Zimbabwe department of social anthropology, Centre for rhetoric studies, University of cape town

Masuku, J (2011): The Public Broadcaster Model And The Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation (ZBC): An Analytical Study, Master of Philosophy Thesis, Stellenbosch University

Mawere T (2015) Decentering Nationalism: Representing and Contesting Chimurenga in Zimbabwean Popular Culture. PHD Dissertation. University of Western Cape

Mbembe, A. (2001). On the post-colony. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Mboti, N. (2009): 'Hollywood, TV, US': A Non Western Gaze, DPhil Dissertation, University of Zimbabwe, Harare.

Moyo, D. (2004). From Rhodesia to Zimbabwe: Change without change? Broadcasting reform and political control. In H. Melber (Ed), Media, public discourse and political contestation in Zimbabwe. Sweden: Elanders Infologistics vast.

Muchemwa C, Ngwerume E, and Hove M, (2011), Misleading Images: Propaganda and Racism in the Politics of Land in Post Colonial Zimbabwe, International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, Vol. 1, No. 19, page 220-222.

Muwonwa, N. (2011) Representation of Nationhood in ZTV Documentaries and Dramas: 2000 – 2009, MPhil Dissertation, University of Zimbabwe, Harare

Ochoa, O. (2000) Comunicación política y opinión pública. México: McGraw-Hill.

Sambo K etal (2013): “Making Seeing Visible” The Question of Visuality in Third Chimurenga Music. Unpablished article.

Shea, D.M. (1996). Campaign Craft: The Strategies, Tactics, and Art of Political Campaign Management. Westport: Praeger

Standler, R. B. (2005). Propaganda and how to recognize it. 1-12. Retrieved March

14, 2016.

Stevens D (2012) “Tone vs Information: Explaining the Impact of Negative Political

Advertising” 11 Journal of Political Marketing 322 - 352

Pour citer ce document

Ce(tte) uvre est mise à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International.