- Accueil >

- Browse this journal/Dans cette revue >

- 4/2015 Media in South Africa/Les médias en Afrique... >

- Varia >

Filming employees in video-meetings: questions on a methodology focusing on image and sound capture

Résumé

Cet article présente une recherche sur les usages de la visiophonie en réunion d’entreprise. La méthodologie utilisée observe les salariés avec une captation d’images et de sons au sein d’une entreprise industrielle. Un nouveau lieu semble se créer par la télé-présence. Les interactions par les corps l’emportent sur les interactions par le regard. Cette recherche-action vise aussi à questionner le statut des images et des sons au sein d’une méthode d’observation et d’analyse de la communication d’entreprise.

Abstract

Analyzing the uses of video-meetings and videophony required a collaboration with industrial companies. A specific methodology was adopted to observe employees, using image and sound capture within the company. A new and virtual place seems to be done by telepresence. Telepresence is a means of exchange where bodies speak to each other and interact more than eye gaze. Finally, this research aims at raising the question of the status of film and images as methods of observation and analysis in business communication.

Table des matières

Texte intégral

Introduction

1‘Thanks to camera phones, we can share images of our lives more frequently and more quickly, sometimes even instantly: life streamed ... Nowadays, when we witness an unexpected event, chances are it will be our camera phone that we will use to document it’ (David, 2010: 89 in Lillie, 2012: 81).

2Sometimes such studies are made with a special focus on a company (for example Nokia in Lillie, 2012) but they are almost done in the private sphere. Images in institutional communication are of interest to researchers but images of images’ uses in the professional environment are too rarely studied and shown. One of our research aims, using anthropologic video of web-meeting in industrial companies with webcams or mobile phones, was to contribute to reduce this lack. Furthermore, we wanted to highlight the notion of spaces and the sensory spaces of each interaction making the assumption that the screen was becoming a space, was ‘lived’ sensorially as a space and a place. We believe that the ‘site of engagements’ is not just where the interaction takes place but that it underscores the interaction itself (Scollon quoted by Paul White during the IVSA Conference in Cumbria in 2009). To answer to the social demand of new knowledge about videomeetings, a research team has the opportunity to take advantage of a regional context.

3The decree 2006-1109 transformed the University department ‘Activities in the service sector’, to which our research Unit (G-SICA / Groupe inter-laboratoires Sur l’Image, la Communication et les Arts numériques) is attached, into the Institut de Management de l’Université de Savoie. Initially, a Professional University Institute (IUP) was created on the University campus in 1991. Strong ties were created early on between the University and businesses close by with the support of a Business Club, initially called ‘Institut Supérieur des Entreprises’. Today1, the Club includes more than forty French and Swiss companies and has become an integral part of the University with a number of employees and offices within the building. This choice attests to the strong relationships that have been established as a result of the fusion of business professionals and a public University Institute. Apart from management science, the principal and longest running research discipline, researchers in information and communication science, were able to launch a research project to make a CD on the subject of images and communication in businesses. The interactive research was aimed at both a public interested in the possibilities of image concepts and technologies, and a public of business professionals interested in the uses of images. After the public presentation of this first work to an employees’ association, business decision-makers asked that companies and research units collaborate on research into contemporary communication practices. This request led to the beginning of an action research as drawn up by Laramée and Vallée (1991).

4 This first work has consolidated the contract between businesses of the Business Club and the University (and its research Unit) and has given rise to a joint research project on Tele-Presence with Images and Sounds (T-PIS) and its uses in businesses. To encourage research into T-PIS, which is the central subject for the G-SICA research group, in a professional, private, and social sphere as well as in the artistic field, we have drawn up a new research project associating theBusiness Club. This project has been approved as ‘Bonus Qualité Recherche de l’Université de Savoie’ and is financed by the University and the ‘Assemblée des Pays de Savoie’.

5 Analyzing the uses of video-meetings and videophony required a collaboration with companies to answer questionnaires about equipment and meetings. A specific methodology was also adopted to observe employees, using image and sound capture within the company. Recruiting a body of companies interested in working with the researchers was greatly facilitated by the partnership with the Business Club. A request to film on site was then accepted or refused by some companies.

The body and videoconference studied in a business environment

6The first sociological studies of videophony were published in 1989 in the wake of the ‘the Biarritz experiment’ that was carried out in France from 1979 to 1984. Indeed, in 1979, the city of Biarritz is chosen by the French government, represented by Direction générale des télécommunications, to be the place of one of the first world experimentations of fiber optic in access network to home (FTTH, ‘Fiber To The Home’). More than 1300 households are involved in the content reception experience (thematic TV channels, video on demand) but also to the very first uses of videophony (Cassagne & Gayan, 1983). Two research studies can be mentioned here, beginning with observations on private use in a family circle by Francis Jauréguiberry (Jauréguiberry, 1989) showing how the videophone was adapted to serve communication between close family members helping to reduce feelings of absence. We can also mention Michel de Fornel’s first article published in 1994 addressing the interactional framework of videophone exchanges which, starting from Goffman’s interactional approach in communication (1967), specifically highlights ritual interactions at work during videophone exchanges (compared to telephone or face-to-face communication). This precursory work focusing on the details of private videophone communication led us to move the subject to an organizational setting.

7 A network of French researchers is currently working on the subject of videophony (Licoppe and Relieu, 2007; Morel and Licoppe, 2009), including a study of videoconference opening and closing words and greetings (Relieu, 2007), and statutory methods of image exchange within legal hearings at a distance (Licoppe and Dumoulin, 2006). The study has led to the development of a methodology based on the simultaneous use of audiovisual codes and conventional analysis (to be published in the French review Réseaux). Even though the organizational context was taken into account, unlike the work by ‘pioneers’ on the subject, this research nevertheless produced artificial observation conditions of uses, as the experiments on which they are founded were carried out in R&D laboratory conditions or directly for the commissioners of the project to develop videophone technologies.

8 In addition to the ‘general’ practices of video-communication in organizations, the research presented here also led us to study embodied practices of distance communication. The different modes of communication are complex in a sort of 'intersituativities' (Hirschauer, 2011). Internet development produces unknown changes in social practices. More than the mail, the telephone or the mobile phone, Internet enhances the interpersonal communication at distance. As the payment does not depend on to the real time of the communications, the use of Internet is almost completely free. This feature of the web communication enables a telepresence that can question the concept of the distance. Webcams and softwares like Messenger enhance new social practices allowing more and more contemporary users to spend more time at distance than in face-to-face interactions (in private and professional spheres).

9 This question of the place of the body in organizations was tackled by a research group that insists that the body dimension is necessary in order to understand organizational activities:‘The organization is an embodied practice including the importance ascribed to its presence in practices of organizations and the effects that this ascription produces’ (Casey, 2000: 2).

10However, the subject still remains little developed in French research. A paper by Françoise Bernard has contributed to reducing this lack postulating ‘the importance of the body as the most important factor of relations’ (Bernard, 2007). At a time when images are a preoccupation with businesses, as research projects on the subject are the object of keen requests in the Rhône-Alpes region, this question of the body in images and video requires deeper reflection to determine new or specific competences to use in professional visual exchanges.

Progressive and reflexive methodology

11‘Mobility-oriented social science highlights the importance of investigating how worlds (and sense) are made in and through movement’ (Buscher and al, 2011).

12Finally, this research aims at raising the question of the status of film and images as methods of observation and analysis in business communication and will be carried out on two levels:

13- work on the nature of the results obtained from capturing images and sounds in organizations linked with other methods (liberties and constraints). As Antonio Strati notes

‘the methodological issues raised by the analysis of the visual... are both subtle and important to aesthetic approach. They highlight that understanding all life based on aesthetically produced documents (e.g photographs) is a delicate and complex matter, whether they are produced by the all actors or whether they are an artefact created by the researcher’ (Strati, 2000: 27).

14- study the role of hypermedia subsequently as a ‘perfectible cinematic expression of research’ (Friedman, 2006: 6) or even a means of ‘image’ restitution in research on images making us the proposition of Sigrid Norris: ‘embodied and disembodied modes of communication are employed by social actors in order to communicate complete messages, which often integrate several conflicting messages’ (Norris, 2004: 65).

15In addition to images and sounds, the chosen field here also leads us to examine the role of the network in research and to consider the reflexion of the researcher and his subject and methodology. ‘

‘Ethnography was created to destabilize, but it is entirely possible that a routinized form could emerge. We wonder whether the enchantments that ethnographic practices deliver will survive as the institutionalization of corporate ethnography itself becomes greater, and descriptions of whatever this job is becoming clearer. If the work is routine, no one is disrupted’ (Cefkin, 2009).

16In particular, we retain the contributions of the conversational analysis (Goffman’s interactional analysis) and the sociology of uses (De Certeau, 1980) from previous research. Thus, in order to observe and try to understand at distance communication practices, sociology of uses is very useful. It allows us particularly to discuss both the strength of technologies and the public participations. We also consider ‘resistance’ situations (De Certeau, 1980; Perriault, 1992) when the technological device, initially thought by designers imposes itself rather with social demand than with technological functions. Here, the different media and multimedia imaginaries can be explored through the history and the evolution of media perception. Indeed, as it has been shown by the past in media practices and cross-media approaches, at distance communication and face-to-face communication are rather complementary than opposite. In continuity, the video conversations through the screen have been analyzed, both by observing people experimenting T-PIS but also by interviewing them before or after the sessions with cameras. This method allows us to question and to highlight the complementarity between visual anthropology and sociology on the special issue of screen’s practices in professional area. The detailed analysis of rushes allowed us to understand the ritual behaviors that were spatial and corporeal, but also the people relationships with their places and material environment.

17The addition of applied phenomenology to electronic networks (Weissberg, 1999; Introna, 2004) has led to a specific problematic which, for example, questions objectives that T-PIS users can draw up.

‘Phenomenological understanding is an array of new experiences and descriptions that make sense for us in our daily activities. These insights make sense for us as they are considered appropriate in terms of our coherent work, functioning, and everyday life, we apprehend them and make them elements of our being. By this we mean that the screen, in order to be a screen, assumes in its screening a referential that is already shared and is full of language, symbols, practices, beliefs, values, and so forth, for its ongoing being’ (Introna, 2004).

18According to Strati (2000), this point of view is similar to the historical proposition of Husserl. The original constitution (‘Urkonstitution’) of the ‘thing’ is developed in his theoritical lesson on ‘passive synthesis’ by the founder of the phenomenology. For the theory, every material object has specificity in the beginning of the process. The phenomenologists must ‘describe’ the acts of experience and their complex connection with the perception of sensible reality.

‘The merging and close interconnection of reified human feeling and the “thingly” dimension which appears to be indowed with its own sensibility. The difference of feeling in organizations does not exist over and above the “thingliness” of organizations. They are not the synthesis of some speculative and ideal procedure. They are “things”, and aesthetics renders them knowable in their being-different by observing their actual use in the day-to-day routine of an organization’ (Strati, 2000).

19The field of aesthetic of communication helps us to understand ‘the social relation phenomena from a contact and sensitive link viewpoint’ (Caune, 1997: 6). Compared to formulated research, audiovisual and sound capture calls for audiovisual aesthetics and semiotics, even though the collectors of these images and sounds are not audiovisual professionals. For example, the signification of ‘off screen’ is relevant in the context of organization communication. Visual anthropology methodology could be particularly adapted to observation because ‘images are able to follow the continuity of body movements and facial expressions’ (Fieloux and Lombard, 2006: 26) and furthermore we are thinking:

‘The body as the channel of the social identity (...) as it is possible to see how the body is in representation and how it is animated by the reception act (...). The body, as expressing feelings, emotions and desires’ (Martin Juchat, 2008: 5).

20The role of visual methods is to help us for understanding main evolutions in the landscapes that are concerned. This situation obliges the researchers to innovate both in epistemology and methodology. A methodology borrowed from the field of visual anthropology and hypermedia (Pink, 2003), culminating in an anthropological film for another research project carried out by the G-SICA group, has led us to also apply it to a professional context. One of the advantages of visual anthropology is that it represents:

‘a collaborative approach that demonstrates how many aspects of experience and knowledge are not visible; and even those that are visible will have different meanings to different people. Finally, visual anthropologists view image production and the negotiations and collaborations that this involves as part of a process by which knowledge is produced rather than as mere visual note taking’ (Pink, 2003).

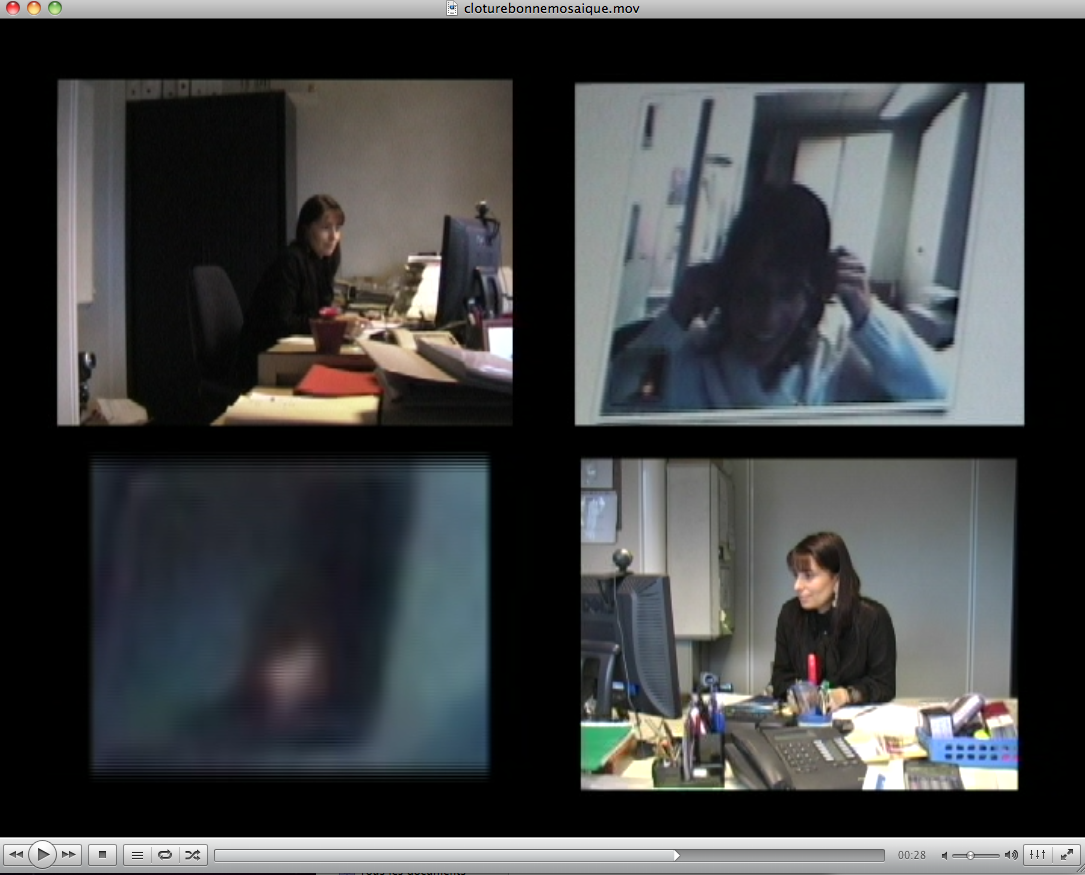

21The body of images from speakers’ screens would not be sufficient to try and answer research questions, as in the case of research methodologies that exclude visual anthropology. In our research work in a videophone communication at distance between two employees from an industrial company, we opted to use exclusive material from image and sound capture, although very few methodologies about organization communication include images (Bouzon and Meyer, 2006). This decision was to integrate a multimodal analysis (Norris, 2004: 13). Moreover, it could be a real opportunity to film the body at work when the cultural and general context mobilizes more and more the body in society. Technical gesture could be highlighted, new modes of experiences and multiple identities (Andrieu, 2011) could be observed. Bodies at work could also express emotions at work and the multiple ways of being in businesses (personal development and coaching, self-respect or, on the contrary, moral harassment, physical pains,...) (Coutarel and Andrieu, 2009). We filmed one speaker from different focal points during a conversation exchange about purchasing products. Then, a four-screen synchronized mosaic was created using the four recordings (Figure 1). This mosaic served as both an element to help research and a piece of iconic material to be used in an anthropological hypermedia piece currently under production and considered as a research in itself, and comparable to a scientific article.

22The visual and bodily data will make it possible to research into their corporeal sequence according to a grid resulting from action ethnography (Piette, 1996). The details within the interactions are taken into account in the interpretative richness of their apparent smallness (Figure 2). This type of ethnography is well suited to situations where the subjects observed are in a face-to-face situation but does not apply in a T-PIS context where there is no face to face contact. The contribution of virtual ethnography (Hine, 2000) for distance communication therefore proves to be determining as a disciplinary complement in the progressive and especially reflexive development of our methodology in communication research (Mucchielli, 2005) and in the diversity of the conceptions of research on organizations in information and communication science (Bouzon, 2006).

23Through our inter-disciplinary choice, we work in a ‘new climate’ in which

‘visual anthropologists have continued to produce new, innovative, reflexive, and theoretically informed projects using photography, video, drawing, and hypermedia. This new work has developed not out of thin air but as the outcome of a sub-discipline’ (Pink, 2003).

24 The research team was developing a way of epistemological reflexivity. Producing a film and building a visual method with the researchers and the participants like Coralie and Valentine were an engagement of reflexivity (Pink, 2009). The visual methodology of this research has an intrinsic goal of reflexivity to contribute to ‘an interpretative social science that is simultaneously auto-ethnographic, vulnerable, performative and critical’ (Denzin, 2001). Thus, that is reason why our research is also revealing the closed collaboration with the participants, the trust we had to build gradually about the use of the visual in organizations, all of that in respect with the field of ‘participatory methods’ (Pink, 2007). Indeed, new understandings of digital practices have been coproduced with participants, who agreed with the use of the camera for a research based on organization communication. Users participated as users of a digital device (T-PIS here) but also as actors of a research process. Ethical relations between researchers and business actors are particularly tricky, especially when they concern the video introduction into the organizations. That is reason why the participants were continually informed by the research evolution and have been placed in front of their own images through the video-mosaics. But somewhere, we would like to notice here that this kind of shyness with the use of a camera into companies often reveals how the research can become an action or an intervention into companies. It becomes a way to listen and to catch people’s stories of organizations and to grant them a form of recognition into their institutions.

25Furthermore, the practices of video-meeting that we are expected to describe here needs to be observed in details because the videophone communication at distance is organized around several and complex modes of communication (Morel and Licoppe, 2009). It means that there are the visual but also the corporeal modes, the sounds but also the texts, the touches but also the voices modes. Thus, facial expressions, places of the body in front of the screen, contents of the screen during the video-meeting, all the background will have to be recorded in parallel with participants’ conversations.

The video-meeting

26 To illustrate the methodology, we will present the practical case of a filmed webconference between Coralie and Valentine, two employees from an industrial group in the Savoie region. The choice of this industrial group is the result of a long process of presentations in front of managers and members of the Business Club. After numerous meetings in head offices of companies to explain the project of research with the necessity to catch and to record work everyday life, we received a majority of negative answers and a few positive responses. The explanation of these decisions is not in relation to the question of the respect of the confidentiality but the problems of IT Security and shooting faces of salaries and fear about their potential and external utilizations out the sphere of research. In this industrial group, the human resources manager accepted the principle of the cameras in the company with the condition of free acceptation of employees. In the little group of real and regular users of professional webconference, Coralie and Valentine were volunteers. They could participate to this qualitative research with a goal to experiment a visual methodology about visual use.

27This meeting is part of a communication rite set up between the two women who, during Valentine’s trips to Paris, are accustomed to communicating by videophone. The industrial group has associated with a Parisian brand before collaborating to buy products. The object of the meeting is to show samples of products for which Coralie, head of sales in Savoie, needs precise references from Valentine, who is based in Paris (Figure 1: screen upper right), before ordering products from a supplier abroad. The sequence shown here on four screens is taken from the end of the web-meeting.

Figure 1: web-meeting between Coralie (Savoie) and Valentine (Paris)

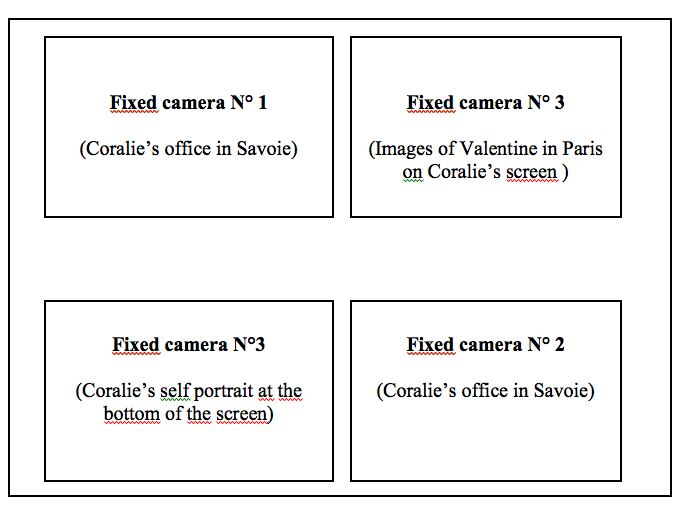

28The four windows of this mosaic show four different viewpoints that can be represented with the following figure:

Figure 2: Place of the four cameras during the filmed sequence

29

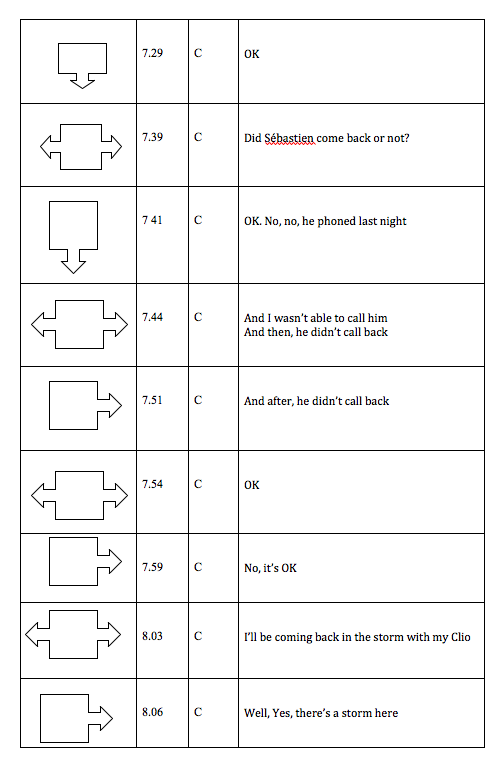

The four sequences filmed simultaneously from four different viewpoints are then subjected to detailed decoding (Figure 4 necessary to the development of Figure 2) following Piette’s proposed method of analysis in order to highlight constants of body postures. The postulate being here that the film ‘directs people’s gaze to useless details like a light, an intonation, a silence, an expression or a gesture which carry more human or social significance when no words are used’ (De Latour, 2006). In respect with interaction analysis, the multimodal transcription (Norris, 2004) of the closing sequence allowed us to take into account several modes of communication like verbal expressions but also embodied practices (head movements, body position, postural direction, hand and arm movements, gazes) and disembodied ones (duration, relation to the time, atmosphere in the office of each employee).

Figure 3: closing sequence

30Running time: 0’37’ from 7’29 to 8’06

31Valentine’s eye gaze and head

32Coralie present on the screen: C

33First Comments:

34Looks in direction of webcam are minority

35Movements Average: 1 / 3 seconds

A virtual co-presence

36 Analysis of the conversational sequences in the observed video-meeting via webcams reveals initially that in a business context the participants of a video-meeting start off their interaction by a simple ‘hello’ generally followed by a sequence of greetings similar in continuity with the telephone (De Fornel, 1994). The meeting is concluded however by a trivial conversation which tends to last longer than by telephone as if we did not know how to end a conversation at distance (Relieu, 2007). The means of communication related to closing video meetings is more phatic and relational than informational and expresses a notion of pleasure and a fascination for the ever present screen (Introna, 2004). Moreover, we can note that thematising the act of ‘seeing’ is important during a video-meeting at key moments of the exchange: at the beginning when the participants need to know that they are recognized and being seen and also when the products are being shown. The remainder of the time, the technological conditions of the exchange are totally ‘forgotten’, unless potential technical hitches such as sound and picture loss or reverberations occur that quickly remind the participants of the technical setting of the meeting. By focusing on the embodied movements in front of the screen, we realized that the distance between participants became more ‘private’ during the web-meeting (in connection with Hall’s proxemic, 1966). Indeed, Hall has shown that the distance between the participants during interactions could give informations on the types of activities and of relations between individuals and that people had delimited spaces in their relationships with others. Thus, he has identified four spheres of communication around people based on their proximity (intimacy, personal/friendly, social/professional, public). Here, the participants use the full screen to receipt the image of their at distance collaborator who is placed at distance in another place. It is just like if the screen and its ‘haptic attraction’ improving by the big shot, allowed the two participants to experiment a mode of communication and a mode of presence which introduces more proximity than expected in the socio-professional context. Just like if it introduced new modes of attention to the other.

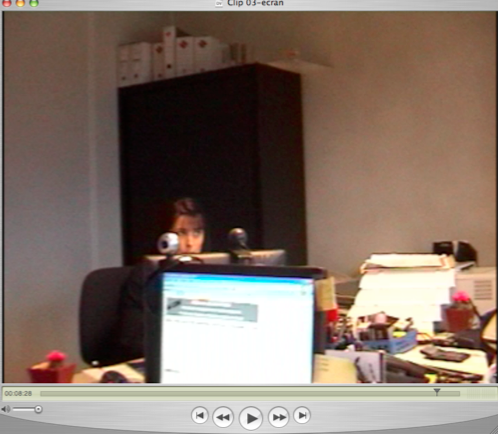

37 We can also note that both speakers tend to isolate themselves from their immediate environment and ‘forget’ it during the video-meeting (see first sequence), as if they had entered a new visual sound space of co-presence. It clearly appears here that ‘all interactions take place in the material world and the material world plays a role in every interaction’ (Norris, 2004: XI). They are fully involved in their visual interaction just as in a face-to-face interaction where People who participate in a conversation must be involved (Goffman, 1967). More than ever, this video communication implies a real ‘engagement’ in the conversation but also new ‘interaction rituals’ -to quote Goffman. Such paradox is coming both from the tradition of face to face communication (e.g. rules greatings, times of speaking, silence that are still important through the webcam) and also from the setting of the interface in a case of a projected image on the screen (attention and fascination phenomena that are linked to the relationships with an image). We observed, with this image appearing among other personal and material contents, that it was a way to bring the other into its own space somehow.

Figure 4: Coralie’s work environment

A non conventional body image

38 The videophone offers ‘a communication experience where we see ourselves communicating’ (De Fornel, 1994). Instead of an excessive use of the control key allowing participants to control their image and thereby their professional positions by ‘good framing’ (Jauréguiberry, 1989), we can note that, on the contrary, the participants do not seem to be preoccupied with their self-image. This disinterest is very visible when analyzing the participants’ ‘self portraits (profiles)’ displayed at the bottom of the screen which are in both cases badly framed, presenting a face that is poorly lit and off centre or only partially represented at times leaving large unoccupied zones in the frame. Some researchers talk about ‘speaking heads’ in the screen (Morel and Licoppe, 2009: 183). This general ‘bad framing’ leads to a derealizationof the body in the sense that the aspect of the person is modified. Furthermore, we can note that the image of Valentine who is at a distance on the screen of Coralie in Savoie is relatively little. Indeed, Coralie did not zoom in the window as we can see it on Figure 5.

Figure 5: Image of Valentine on Coralie’s screen during the web-meeting

39This confirms the idea that virtual co-presence is not based on a conventional and figurative (iconic) representation of the body or another person’s image (facing the camera as in photographic portrait poses, or set poses like TV presenters) but more on an indicative representation (the important point being the indication of the other person’s body). It is also possible that the employees were unaware of the codes of visual representation. On the other hand, we can note that bodily mobility is very much reduced throughout the web-meeting, as though the participants felt obliged to stay on camera. A private sequence illustrates this well when one of the participants goes to check information on a contact in her mailbox, momentarily hiding her video-image window; she begins to relax her body by shrugging her shoulders or flexing her fingers and the tone of her voice also changes.

Figure 6: in this private sequence we can see Coralie relaxing her body

40 The body relaxation during the video-meeting could be correlated with a (false) impression of temporary visual absence by the user generating the private sequence. In fact, as she no longer had a video indication of the presence of the other person, she forgot that she could still be seen via her webcam that was never cut off during the sequence in question.

41 In our case, observing eye gaze in videopresence also reveals characteristics specific to this means of exchange. Firstly, speakers at a distance continually gaze all over the screen. They are forced to continually look at the screen without focusing on a particular point. This ‘screengaze’ is the result of the difficulty (impossibility) of a direct gaze in videophony and videomeetings. Speakers are unable to directly look each other in the eyes, which is sometimes interpreted as an ‘eye gaze in videophony being dysfunctional giving a ‘two-faced’ gaze effect’ (De Fornel, 1994). Contrary to face-to-face exchange, telepresence is a means of exchange where bodies speak to each other and interact more than eye gaze.

42 A sequence of notes taking shows that there is a type of unconscious body imitation between the two participants. Indeed, Coralie says to her colleague at a distance that she needs to take notes, just as it would be necessary to inform her that she would have to lower her head. We observe then that Valentine imitates her by lowering her eyes and head during all the note-taking time. This also occurs at the end of the private sequence when Coralie engages in the visual conversation back. We can see that she sits up and that Valentine imitates her with the same body movement.

43 Finally, body language has become ritualized due to the constraints of showing or demonstrating products at distance. The speaker showing the products uses almost mechanical gestures so that the products will be in front of the webcam, filmed and therefore retransmitted to her counterpart. People who interact in video-meeting take care of technical features that they would not mind in face-to-face interaction (Morel and Licoppe, 2009: 171).

Figure 7: Coralie showing products to Virginie

44 This strongly coded body language confirms an instrumentalisation of professional video-meetings where the latter ‘is often lived as a “structuring” and supposing more abstract and formal relations’ (Chabert and Ibanez Bueno, 2006).

45This is also in line with a communication experiment turned intentionally towards the needs of the other person.

Conclusion

46 This research promotes an approach by images and filmed material as an expression of the research and, it is this unique and rich characteristic that we will try to explain as a conclusion.

47 Firstly, iconic, audio and interactive results from the action research are also intended for organizations. The resulting hypermedia will show both images of the uses of the research object and the stages of research. This multimedia medium will therefore be the joint expression of the filmed and assembled results of the research and the methodology used by the researchers who, loyal to their visual anthropology and reflexive approach, were also filmed while filming users filming themselves (Figure 5) and during their own web- meetings.

Figure 8: the researcher in the organization and camera 3 in place (front-on shot)

48The multiple viewpoints enabled the researchers to film continually the two participants, recording their reactions and body movements. But it is also very important to record with images and sounds the very particular ‘atmosphere’ in each participants’ environment to provide ‘ways of sensing place, placing senses, sensorially making place and making sense of place’ (Pink, 2007: 243). The special issues of place and of relations between users and their immediate environment are taken into account thanks to the multiple cameras filming simultaneously the different scenes of the web-meeting. The reflexive method allows the researchers to immerge more sensorially in the studied places and uses. It allows them to experiment different points of views too (Andrieu, 2011), that can be revealed by the visual method. The integration of video in an anthropological method of communication

‘can serve as a catalyst for creating ethnographic understandings of other people’s experiences and representing these experiences to a wider audience. (...) The advantage of filming is that it invites empathetic engagement with the sensorial and experience body of the film subjects in their viewers’ (Pink, 2007: 245).

49 Secondly, transmitting the results iconically to the organization and putting them back in situation will change the research into action to support changes within this organization (Van Cuyck, 2007). The followed approach will make visiblewhat can be termed invisiblesocial practices for both research in social and communication science and businesses. The hypermedia elements produced and shown within the company offer an account of practices that had remained hitherto underground. It gives them direction in the context of the organization; democratizes them and makes them understandable (Delcambre, 2007). Images that can sometimes be more powerful than words constitute here a type of ‘report’ on situated employees carrying out their professional activities. In line with other researchers we believe that the writing of images ‘that approaches individuals, that reach other’ intimacy by means of their social expression, (...) make it possible to build new facts and new spaces of intelligibility’ (Fiéloux and Lombard, 2006: 25). These constitute an attempt to demonstrate, using images, the development and professionalization of webcam use in companies that ‘goes against the representations initially tinged with fears on behalf of the management’ (Chabert and Ibanez Bueno, 2006). Basically it makes visible the ways of working today in industrial sphere, the way of collaborate, the relations to the layout and materials in the environment (with the use of the screen in both production and reception of images or the use of the webcam)... all ‘aesthetics experiences, universal, embodied, sensory and modes of human beings’ (Warren, 2008: 569). It also enables us to approach the issue of feelings and desires, the issue of pleasures in working practices, of dreams and evasion in different worlds. It’s a kind of review of ‘non-rational’ elements of human being at work (Warren, 2002). Here, in tradition with some documentary anthropologists, we attempt ‘to show not only what people are doing but also their imaginary’ (Rouch, 1960) and thus to tellthe story of the organization through images and sounds, embodied and disembodied practices. The short- lived images self-produced by individuals with their webcam, in respect with a chronology (a beginning and a close session), a setting (3 different spaces), an intrigue, playing by ‘actors’ more ‘creactors’ than passives, propose a kind of ‘interactive narration’ (Manovich, 2001). This observation lets us think that such ‘self-narratives’ images, reflexive images, are able to tell the life in the organization.

50 The hypermedia anthropology with the production of interactive films, online images in movement or photographs, permits anthropologists to understand more in depth these new social practices. Images reflect a further aspect of the Internet visual culture. Such a research is constructed as a kind of ‘image-text’ (Warren, 2002: 238) where neither words nor images would be adequate alone but where ‘viewing an image may carry more communicative meaning than reading a description of the very same thing (...). The image has more “reality”’ (Norris, 2004: 2).

51 Thirdly, the ins and outs of a research using fragments of images obtained from companies require a more delicate understanding between researchers and the organization than traditional research in information and communication science. This negotiation is necessary both for the methods of collecting the images and the methods of showing and/or publishing the images of the company and its employees. Here, the video recording can play a role in stimulating social interaction between interviewers and respondents. Some companies interrupted the research process more or less radically when they realized that employees would be filmed in video-meetings, invoking arguments such as company confidentiality concerns or the lack of time to organize this type of meeting. The process is long; there are many obstacles to overcome and agreements to be obtained. A relationship of trust must be created with the actors on site, regardless of their status within the company, especially when trying to obtain the authorization to film. We feel that the management gave us their authorization in order to reassert the institutional or organizational image of the company and with regards to employees improving their professional activity within the organization. In this respect, the fact that researchers came on site in order to set up a type of ‘mobile research unit’ with film-making equipment installed in the participants’ offices both intrigued and gratified them in the eyes of their colleagues.

52 Finally, we propose that, after agreement from the company, the rushes collected in this study could be used as an argument to convince future companies to allow researchers to film. We got the trust of other companies2 faster before this research, just by showing the results with images. These images can give body and reality to a piece of research better than any words as aesthetic experience. This experience is not reducible to language. This can enhance a model of collaboration in research, in other words a research where ‘meaning is actively created in the interaction between the researcher, respondent and the image’ (Harper, 1998: 35). The research team has developed a non-definitive and participatory methodology including aesthetic ethnography with the participation to the individuals’ reactions, ‘a contact and interactive process of reciprocal influence that affects the partners’ (Caune 1997: 7). The researchers are here recognized ‘as a source of data in their own right, and a celebration of research as an aesthetic activity in itself’ (Gagliardi, 1996 in Warren, 2004: 229). To paraphrase Samantha Warren: ‘Using a camera in a research project adds fun and novelty to the activity of “doing research” enhancing the aesthetic dimension of research itself for all concerned’ (Warren, 2002: 243).

Bibliographie

Andrieu, B. (2011). Les avatars du corps, une hybridation somatechique. Montréal: Liber.

Bouzon, A. (dir) (2006). La communication organisationnelle en débat champs, concepts, perspectives. Paris: L’Harmattan.

Bouzon, A. and Meyer, V. (dir) (2006). La communication organisationnelle en question: méthodes et méthodologies. Paris: L’Harmattan.

Bernard, F. (2007). La recherche-action dans les travaux consacrés à la communication d’action et d’utilité sociétale : le cas de la communication engageante et de l’environnement in La recherche-action en communication organisationnelle. 2ème journées d’études d’Org&Co. Paris: Celsa.

Buscher, M. Urry, J. and Witchger, K. (2010). Mobile methods, London, Routledge.

Cassagne, J.P. Gayan, L.G (1983). Le câble à Biarritz in Communication et langages, 1983, vol 57, n°57 : 97-105.

Casey, C. (2000). Sociology Sensing the Body: Revitalizing a Dissociative Discourse in Hassard, J. Holliday, R. and Willmott, H. (eds). Body and organisation. London: Sage: 52-70.

Caune, J. (1997). Esthétique de la communication. Que sais-je ? Paris: PUF.

Cefkin, M. (2009). Ethnography and the corporate encounter: Reflections on research in and of corporations. Oxford: Berghahn Books.

Chabert, G. and Ibanez Bueno, J. (2006). Télé-présence avec images et sons (T-PIS) et communication organisationnelle in Pratiques et usages organisationnels des Sciences et Technologies de l’Information et de la Communication. Colloque International en Sciences de l’Information et de la Communication. Université de Rennes 2: 82-87.

http://www.uhb.fr/alc/erellif/cersic/spip/article.php3?id_article=43

Coutarel, F. and Andrieu, B. (2009). Corps au travail. Corps 2(6): 11-13.

De Certeau, M. (1984). The practices of everyday life, Berkeley: University of California Press. Original work published as L'Invention du quotidien, 1. Arts de faire. (1980) Paris: Gallimard.

David, G. (2010). Camera phone images, videos and live streaming: A contemporary visual trend. Visual Studies 25(1): 89-98.

De Fornel, M. (1994). Le cadre interactionnel de l’échange visiophonique. Réseaux 64: 107-132.

De Latour, E. (2006). Voir dans l’objet : documentaire, fiction, anthropologie.

Communications, 80: 183-197.

Delcambre, P. (2007). La recherche sur corpus comme intervention visible dans le jeu social in La recherche-action en communication organisationnelle. 2ème Journées d’études d’Org&Co. Paris: Celsa.

Denzin N. K. (2001). The reflexive interview and a performative social science, Qualitative Research, Sage Publications, vol. (): -

Hirschauer, S. (2011). Intersituativity. Presentation at Centre for Interdisciplinary Studies, ZiF, Bielefeld, May 2011.

Licoppe, C. and Dumoulin, L. (2006). Usages des dispositifs technologiques dans la justice : le cas des audiences à distance in Pratiques et usages organisationnels des Sciences et Technologies de l’Information et de la Communication. Colloque International en Sciences de l’Information et de la Communication Université de Rennes 2: 114-115. http://www.uhb.fr/alc/erellif/cersic/spip/article.php3?id_article=43

Fieloux, M. and Lombard, J. (2006) Explorer et écrire avec l’image. Communications 80: 19- 26.

Friedman, D. (2006). Le film, l’écrit et la recherche. Communications 80: 5-18.

Hall, E. (1966). The hidden dimension. Garden City, New York: Doubleday, Anchor Book.

Goffman, E. (1974). Les rites d’interaction. Le Sens commun, Paris: ed de Minuit. Original work published as Interaction Ritual: Essays on face-to-face Behavior (1967). Garden City, New York: Doubleday, Anchor Books.

Hine, C. (2000). Virtual ethnography. London: Sage.

Introna, L. (2004). The ontological screening of contemporary life: a phenomenological

analysis of screens. European Journal of Information Systems 13(3): 221-234.

Jaurréguiberry, F. (1989). Usages domestiques du visiophone. TIS 2: 89-102.

Laramee, A. and Vallee, B. (1991). La recherche en communication. Montréal: Presses de l’Université du Québec.

Lillie, J. (2012). Nokia’s MMS : a cultural of mobile picture messaging, New media and society 14(1): 80-97.

Morel, J. and Licoppe, C. (2009). La vidéocommunication sur téléphone mobile : quelle mobilité pour quels cadrages ? Réseaux 156: 165-201.

Martin Juchat, F. (2008). Penser le corps affectif comme un média. Dans une perspective d’anthropologie par la communication. Le Corps 4: 85-92.

Manovich, L. (2001). The language of new media. Cambridge, MA: The Mit Press.

Mucchielli, A. (2005). Pour une « approche communicationnelle » des TIC Un nouveau référentiel Sciences Info-Com, Université de Montpellier 3, Montpellier, 2005

Norris, S. (2004). Analyzing Multimodal Interaction-a methodological framework-. New York and London: Routledge.

Perriault, J. (1992). La logique de l’usage. Paris: Flammarion. Piette A (1996) Ethnographie de l'action, l'observation des détails. Paris: Métailié.

Pink, S. (2003). Interdisciplinary agendas in visual research: re-situating visual anthropology. Visual Studies 18(2): 179-192.

Pink, S. (2007). Walking with video, Visual Studies 22: 240-252.

Pink, S. (2009)., Doing Sensory Ethnography, Sage, 2009.

Relieu, M. (2007). Qu’est-ce qu’une technologie transparente ? Une étude des usages situés de modules de téléprésence in Workshop Interaction et Technologie: le cas de la visiophonie. Réseaux. ENST, Paris.

Strati, A. (1999). Organization and Aesthetics. London: Sage. Strati A (2000) The aesthetic approach in studies in Höpfl H and Linstead S (eds) The Aesthetics of organization . London: Sage.

Van Cuyck, A. (2007). La recherche-action, instance communicationnelle et sociale du processus d’élaboration de la connaissance en action in La recherche-action en communication organisationnelle. 2ème journées d’études d’Org&Co. Paris: Celsa.

Warren, S. (2002). Show me how it feels to work here: using photography to research al aesthetics, Ephemera 2(3): 224-245.

Warren, S. (2008). Empirical challenges in all aesthetics research: towards a sensual methodology. Studies 20(4): 559-580.

Weissberg, JL. (1999). Présences à distance – déplacement virtuel et réseaux numériques. Paris: L’harmattan Communication.

Notes

Pour citer ce document

Ce(tte) uvre est mise à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International.